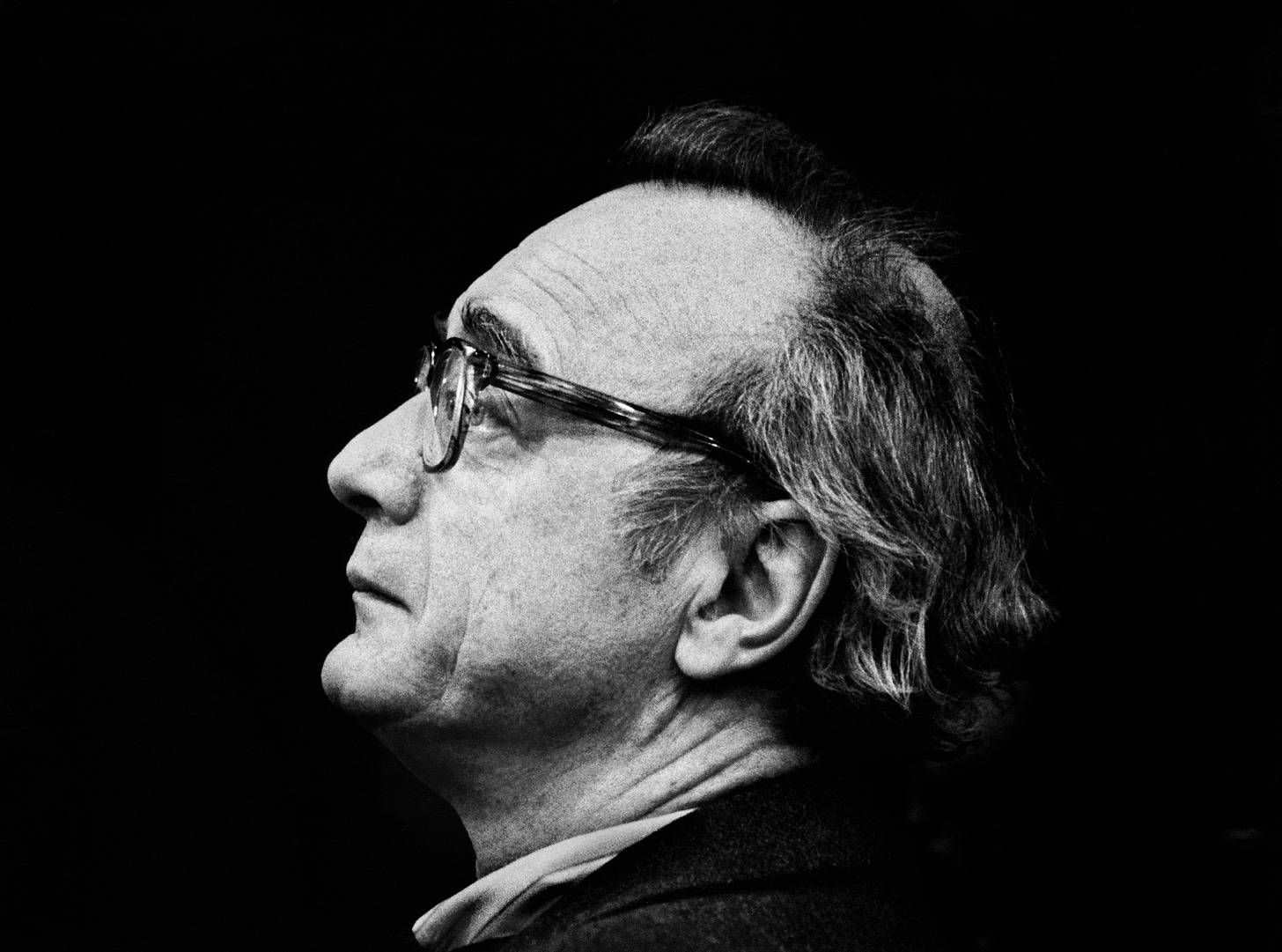

The string wisdom of Alfred Brendel

The legendary pianist, who died on Tuesday, was typically insightful and frank about fashions in string playing

Many musicians have written beautiful tributes to piano legend Alfred Brendel and to the profound impact of his piano playing. I can’t add to that, but can offer some of his own insights into string playing, which he gave me for a BBC Music magazine article on fashions in sound.

I had watched him coach a young group at the String Quartet Biennale in Amsterdam, excoriating the players for using no vibrato or bow pressure in a Beethoven slow movement. This has long been a pet peeve of mine, so I was delighted to hear someone of his stature picking up this issue, and to hear his advice to them. He was very generous in explaining and critiquing the problem for my article, in his typically thoughtful, sardonic way.

Here he describes the style:

‘It is distinguished by very little vibrato, if any, producing a painfully artificial, lifeless sound on long, sustained notes, averse to any cantabile. For quite a few players this has become standard practice in pianissimo sections. The sound, instead of ominous or mysterious, becomes dead. What is lost in this kind of playing is a great deal of warmth, colour, character and nuance. Until the day before yesterday, string players as well as singers made use of various kinds of vibrato – faster and slower, wider and narrower. Fast vibrato seems to have become extinct.’

He suggested that there might be less-than-musical reasons for doing so:

‘There has been a very strong generation of mainly female violinists and brilliant string quartets with whom to compete would have been a tall order. Why not do something essentially different? Something the older generations of players have not done? And isn’t it desirable for the younger players to present a markedly different approach anyway? There is the danger of mistaking musical performance for a series of fashion shows where the newest brands are presented and eagerly absorbed. While a gifted young composer will try to clearly distinguish himself from his fathers and grandfathers, the performer should be the “composer’s ardent servant”, in Schoenberg’s words.’

In a quote I didn’t have space for in the published article, he explained how this way of playing was influenced by a misapplied sense of Baroque style:

‘Is Haydn’s and Mozart’s music deserving of a sound that would suit Monteverdi or Handel? I think not. To my mind, Leopold Mozart’s prescription in his Violin School remains relevant: “Singers who separate each little figure, breathe in, and stress this or that note would cause irrepressible laughter. The human voice connects one note with the next in the most unforced way… And who doesn’t know that vocal music should always be what every instrumentalist has to keep in mind – because one needs, in all pieces, to come as close to being as natural as possible.”

‘For an ambitious string player who is not a member of an orchestra, a personal sound has always been a natural requirement. But does it make any sense when a musician’s personality is split into two: one for the music of the later 18th century, and a drastically different one for the 19th? Some players give the impression that a public decree was issued somewhere around 1801 which from now on prescribes employing vibrato, and playing on steel strings. Beethoven was Haydn’s and Mozart’s younger contemporary. The Schuppanzigh Quartet had already played for Haydn before being at Beethoven’s service. After all, the development of string playing and string instruments from the Baroque into the 19th Century was a very gradual one.’

Ultimately, he told me, this way of playing put him off coaching Haydn and Mozart quartets and made him stick to Beethoven and Schubert. But lucky young players who were treated to his wisdom, and long may they apply his teachings!