Who do you think your violin is?

Have you ever wondered about the origins of your stringed instrument? I visited the Bavarian town of Mittenwald to explore the roots of my own Sebastian Kloz and revel in some niche violin tourism

I recently returned from a trip to Mittenwald, in the Bavarian Alps, on the trail of music and violins for the November issue of BBC Music magazine. It’s a beautiful little town, nestled between titanic mountains that loom at the end of most streets, with the pure turquoise Isar river running through, a stunningly-ceilinged Catholic church in the centre and pretty houses painted with the distinctive regional ‘Lüftmalerei’ (literally ‘air painting’). Men and women go about their business wearing their lederhosen and dirndls in a non-ironic way, tourists wander through the streets eating ice cream, and groups of hikers and cyclists recharge in cafés and bars.

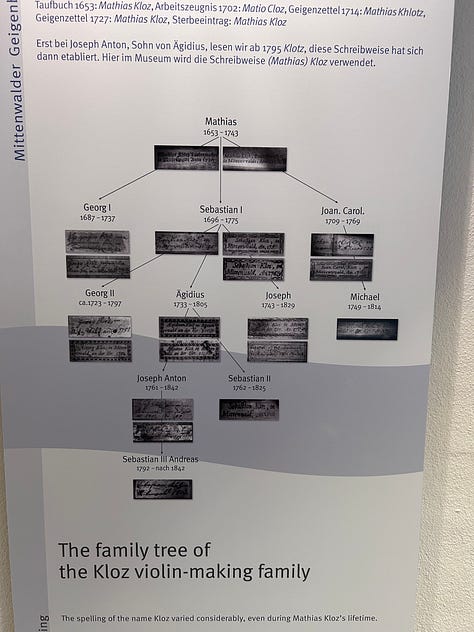

For me, though, the trip was more personal than touristic. My violin was made there in 1758, given life by Sebastian Kloz (1696–1775). (Since around 1795 the name has been written as Klotz but I’ll use the original, as per the label.) Sebastian was the most successful son of Mathias Kloz (1653–1743), who brought violin making to the town in the first place. Ever since I bought my violin 30 years ago from Norman Rosenberg (who aptly described it as ‘a nice little fiddle’) I’ve always wanted to visit. Like a descendent on the trail of their own ancestors and origin stories, I was excited to see the town and investigate my violin’s origins – a musical version of the BBC’s Who Do You Think You Are?.

My first stroll took me to the centre of town and to the statue of Mathias, next to the Church of Saint Peter and Paul. It was built in 1746 and it delights me to think of Sebastian watching it being built. I stroll the streets, spotting violins in the murals and the giant violin sponsored by local associations. I have a Wiener schnitzel outside at the Gasthof Gries, listening to a German guitar duo singing Neil Diamond songs.

The next day, I discover that I had been eating my schnitzel practically outside the home of Sebastian himself. I have an appointment with Anton Sprenger, a luthier and descendant by ten generations of Mathias Kloz, and when I knock on the door of his workshop, he shows me the house a few doors down where Sebastian most likely made my violin.

Inside his workshop, Sprenger offers me a whistlestop version of the Kloz story. Mathias probably went to Venice aged 14 to apprentice in lute making and then worked in Padua for six years with lute maker Pietro Railich (there is an employment reference dating to 1678). He came back to Mittenwald in the 1680s, bringing back the Cremonese inside-mould technique, and set up a workshop. At the time hundreds of new churches were being built, leading to a boom for new instruments. Kloz and his sons would hawk their instruments around churches, royal courts, monasteries and convents, coming back with lists of new customers. Mittenwald was also well-placed as a stopover on the trading route between Nuremburg and Venice.

While Stradivari (1644–1737) in Cremona was evolving his instruments to be more powerful, Kloz instruments suited more intimate spaces but remained popular – it is even thought that Mozart might have played an Aegidius Klotz as a 13 year old, which now belongs to the Mozarteum in Salzburg.

Another natural advantage for violin makers in Mittenwald is its proximity to the local Karwendel forests, which provide dramatic scenery along the train route as well as a ready source of quality tonewood. My next stop was Mannes Tonewood, a relatively new company, which sells local spruce. In tracing the origins of my Sebastian Kloz, you can’t get much closer to the original source than a tree cut down from the same forests – literal roots. With a little latitude you can even imagine that some of the earliest rings of the wood coincided with Sebastian Kloz walking the mountains.

The Church of Saint Peter and Paul is a Baroque extravaganza of gold and cherubs, with a ceiling by Matthäus Günther. Churches don’t usually offer violin geek spottings, but this is Mittenwald, and perched in one corner is a rather uncomfortable-looking angel playing a Baroque violin. Although Mathias Kloz’s statue is right next to this church, he himself worshipped at the more simple St Nikolaus, dating to 1447, down the road, where there is a plaque in tribute, and his remains apparently lie behind the altar. The burial ground surrounding the church also offers a dictionary of German luthiers’ surnames, peppered with generations of Hornsteiners, Neuners and Jaises.

Indeed, it is Georg Neuner, Assistant Headmaster, who gives me a fascinating tour of the Musical Instrument Making School, founded in 1858 by King Maximilian II, which in recent years has broadened to include wind and brass. Having recently interviewed staff and graduates of the Newark School of Violin Making, it was interesting to compare. The course content and teaching style in Mittenwald are traditional in their rules and technical disciplines, where Newark teaching is much freer, and yet the school in Mittenwald is modern in the equipment and technology it offers, not to mention the teaching spaces themselves. Students at Newark, which is facing huge challenges at the moment, might weep at the resources, and maybe more so at the fact that the region underwrites the school in the acknowledgement of its cultural and economic value.

My trip coincides with Saitenstrassen (literally Strings Streets), a music festival offering a rare combination of folk and classical music, which pops up in the buildings and streets of the three towns in the valley. I visit the big tent for the opening night gala, a quintessence of Bavarian culture – beer served in gigantic steins (even to kids), an all-meat menu, potatoes, lederhosen, dirndls and a range of Bavarian folk music, complete with alpenhorns. In the next couple of days I get to sample the range of music, from solo Bach in a tiny church played by Esther Hoppe, to a variety of bands strategically placed all over the town.

On my last day, I’m excited to meet Matthias Klotz, a direct descendent of Mathias and Sebastian, who gives me a tour of the violin making museum. Across two floors, the cases tell the story of violin making in the town, from Mathias and his sons, through the rise and fall of the merchant-manufacturing system that had makers in their front rooms across the town making parts for two big export companies, to Maximilian’s foundation of the violin making school in an attempt to restore the town’s violin making skills and reputation, and bringing the story up to date with today’s makers.

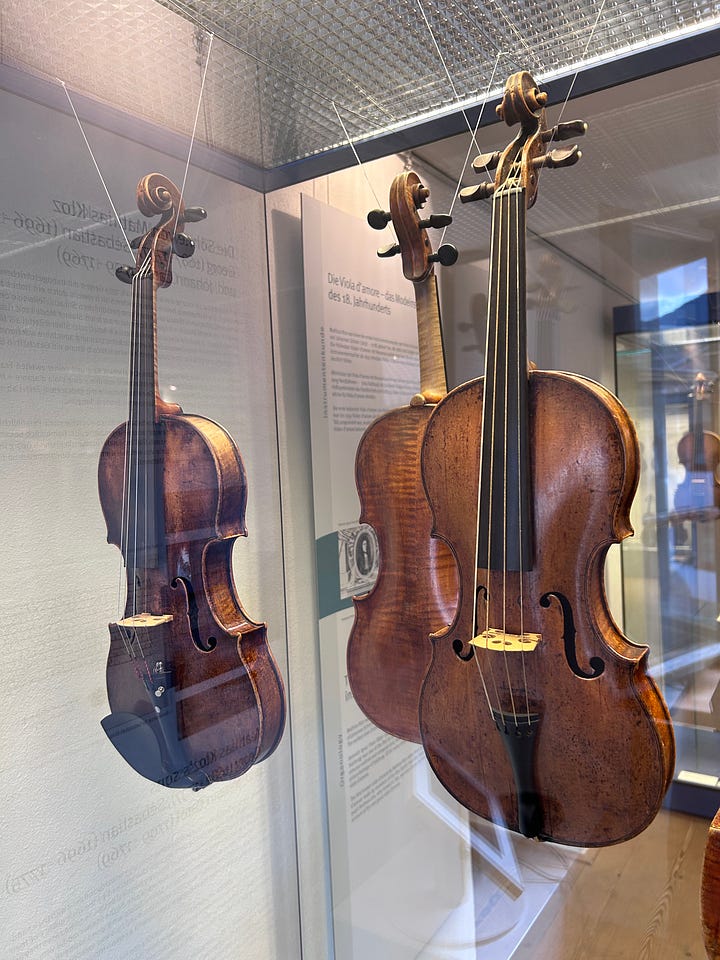

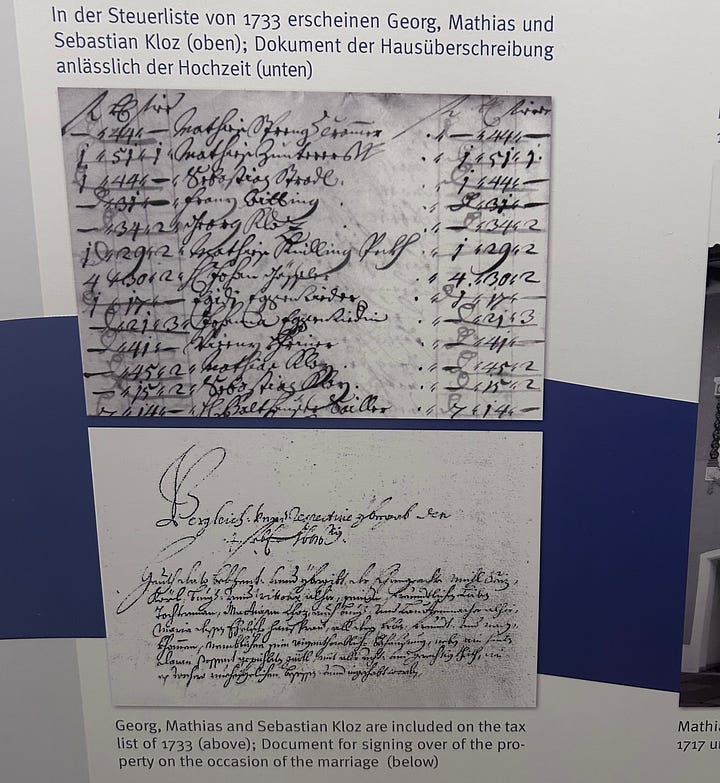

There are cases of violins from across this entire history, including a violin and viola by Sebastian, and a few photographs of documents pertaining to the story, including his name written in a 1733 tax document, which I find strangely moving. In the absence of any more personal relics from 300 years ago, it will have to do.

Pinchas Zukerman once told me in an interview about his special ritual when he goes to Cremona: ‘I open the window and the violin case in the hotel and say, “Welcome home”. I pick it up and it goes, “Hey, thanks for bringing me home. I really sound better now!”’ I didn’t bring my Sebastian Kloz to Mittenwald – the vagaries of air travel with an instrument put me off – but I did take some photos to show to anyone who was interested, including two of his descendants. I breathed the air and saw the building and mountains Sebastian would have looked at every day. I feel I know who my violin is just a little better.

What a fascinating travelogue. I look forward to seeing the piece in print this fall.

As a former clarinetist, I’ve always been jealous of string players, who get to carry so much history and mystery with them in their instrument cases. The Leblanc clarinets I played throughout my career were made just a few years before I purchased them in the late ‘90s!

Just gorgeous! ❤️