The return of Kyung Wha Chung

The legendary violinist Kyung Wha Chung makes her much-awaited London comeback this December, after more than a decade away. On a recent visit she told me about her absence from the stage, her hopes f

There is only one violinist I wanted but failed to get on the cover of The Strad when I was editor there: Kyung Wha Chung. Growing up, I knew her as one of the towering violinists of her generation (a towering generation at that, which included her classmates Perlman and Zukerman among many). Her interpretations of the classics were powerful, brilliant and completely individual. But she seemed to have virtually disappeared from the international stage. I knew she was teaching in Korea and at Juilliard, and there were rumours of a new Bach CD, but enquiries into interviews got nowhere. And then, seemingly out of the blue, the 66-year-old announced her return to the London stage, on December 2 at Royal Festival Hall, the scene of her triumphant debut in 1970.

So I jumped at the chance to interview her when she came to London recently. We met in Kensington, round the corner from the house where she lived for 20 years. She barely seems to have aged from the classic videos of her in the 1970s and, as I’ve often found when interviewing string players, she speaks just like she plays. Despite a throat infection she talked passionately, frankly and volubly, whether about violin playing, classical music, or life and society in general. Her mind sparks quickly in different directions, but always returning to the original question, even if in a roundabout way. She is clearly tuned into modern trends and thinks pragmatically about the future, and yet also comes across as dreamy and idealistic, poetic even.

It’s only logical that Chung’s London comeback takes place at the Festival Hall. It’s there she became an international star, virtually overnight, when in 1970, she was asked to step in at the last minute for Itzhak Perlman, whose wife was about to give birth, to perform with André Previn and the London Symphony Orchestra. There was confusion about which concerto she was to play, with the orchestra ready to perform Mendelssohn and Chung having prepared Tchaikovsky – she recalls the occasion clearly: ‘Previn was very uncomfortable and said, “This is your debut, why don’t I find you another date?” And I said no. We had barely rehearsed but everyone was so concentrated and there was so much electricity. I loved it.’ Her performance (Mendelssohn won out) was brilliantly reviewed and the next day the offers came flooding in. (As Chung says, ‘In those days such a review was really key to a career.’)

‘He was a tyrant. I would work myself to death and he would say, “Darling, if you would only practise. I can take you to water but you have to drink it.”’

Success had been on the cards from a young age, though. Born in Korea to a musical family, she switched from piano to violin aged six and before long was winning competitions. She auditioned for New York’s Juilliard and at the age of 13 the family moved to the US so she could study with Ivan Galamian. He was to become a key figure in her life. What does she remember of him? ‘He was a tyrant. I would work myself to death and he would say, “Darling, if you would only practise. I can take you to water but you have to drink it.” But when we came out of the studio he was a different man: “Come on, why do you look so sad?” Is he kidding? He nearly killed me! He said, “You can do it, of course you can. Patience, patience.” She instinctively goes into his accent and stooped posture when she recounts this. Her respect for him remains enormous, though: ‘He was a phenomenal teacher, born gifted. He knew precisely the mechanics of how the violin worked. He gave me an amazing basic training. He didn’t damage my personality. He was very proud of all his students – Perlman, Zukerman, Rabin, me, Laredo. We all had very different characters, but beautiful techniques. I loved him to death and miss him every second.’

In another decisive moment of her career she came up against Zukerman in the 1967 Leventritt Competition. She had a particular motivation to win: ‘When I was 13 I said to my mother, “Thank you so much for sending me to America, and I promise I will win first prize when I am 19.” True to her word, at 19 she entered the Leventritt, whose jury included the likes of Louis Krasner, Erica Morini, David Nadien, Arnold Steinhardt, George Szell, Joseph Szigeti, Roman Totenberg and Isaac Stern. She describes the burden: ‘I wanted to kill myself. I said, “I’m not ready, but I’ll go for it.” Legend has it that she played better than Zukerman on the day but with pressure applied by Stern, the jury decided to award the prize jointly.

‘There was no pleasure in my achievement. I didn’t dwell on it, I just thought, how do I live up to the expectation of having won first prize. What do I do now?’

She felt little satisfaction from the win: ‘When the prize was handed to me there was no pleasure in my achievement. I didn’t dwell on it, I just thought, how do I live up to the expectation of having won first prize? What do I do now? It meant nothing because I was the same as I had been. People wanted to make me different but I was the same.’ But she was always this tough on herself: ‘I was the hardest judge of myself. Failure was inconceivable. I was very self critical and I didn’t take any compliment to my heart.’ Her solution at this point in her life was to keep studying. ‘When nothing in front of you works, it’s the best time to study. It’s the same with practice. I’d go crazy trying to practise something. Mr Galamian said the best time to study is when it doesn’t work and I tried to realise that. It gives you a free ride because you have to figure everything out.’

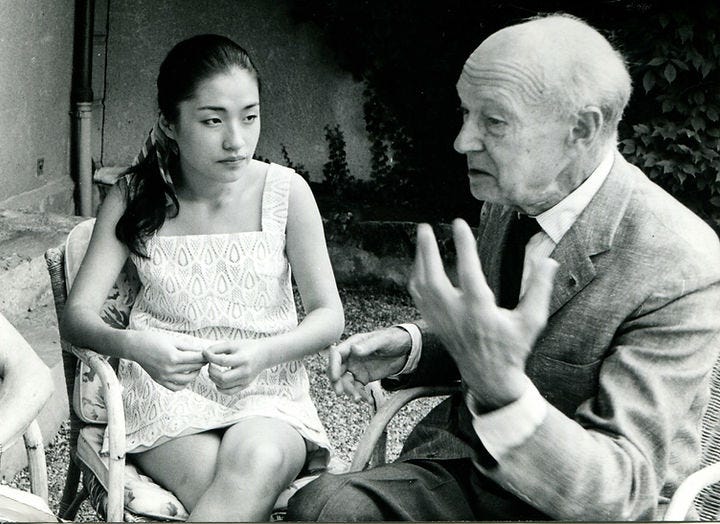

Another great musical influence was Joseph Szigeti, with whom she only studied for eight weeks, but who in that time entirely changed her world view: ‘He opened up a wider vision of violin playing. He put a Chinese poem in front of me. I had read a lot as a child, but coming from him it was different. I felt as if I had been in a great ocean, working so hard to learn this instrument, and then suddenly he said, “Yes, you have to have that, but this is something else, this is what you have to do.” So whenever I travelled I would go to a museum, and do anything I could to connect artistically, diligently, passionately. Little by little things came together. Travelling and putting things together became like a puzzle. When Szigeti opened that Chinese poem, he triggered something and it was enough.’

‘It was shocking. I had never compromised as an artist, because if you do you lose your identity. But if you don’t compromise in a marriage it doesn’t work’

Chung built a brilliant career in the 70s and 80s, with an international schedule and a Decca contract that created classic recordings with collaborators including Previn with the London Symphony Orchestra and Solti with the London Philharmonic Orchestra. But it effectively stopped when she had her first child. ‘My concert life stopped mid-30s when I started a family. It was no longer me or I. It was we, the children, my husband, the family, being a wife. It was shocking. I had never compromised as an artist, because if you do, you lose your identity. But if you don’t compromise in a marriage it doesn’t work. So that was another journey – learning to be a mother and a wife.’

It might sound shocking now, but back in the 60s Galamian, who called her his ‘boy-girl’, told her she must never get married. She remembers, ‘He saw quite a gift in me and every time he saw a gift in female students he lost it because, as he said, “They run off with the boys.” He said I shouldn’t get married.’ But the success of her marriage was a priority, as she explains: ‘Psychologists still say that for a man the order of importance is their career and their marriage. If they lose their career they’re destroyed and feel like a failure. Women want a career and marriage and if they succeed in their career it’s terrific, but if they do well in business and fail in marriage, they feel a complete failure. At least that’s how I felt.’

She also felt under pressure to have children, but senses that this is different now. ‘Things change so quickly. I had my first child when I was 35 and I was an old maid. My doctor was worried that the pregnancy was going to be difficult. Now to have a child mid-40s is nothing. There are so many single people in their 40s, out of choice, or maybe without choice, and it’s acceptable. You can feel comfortable not being pestered. I was pestered when I was past 30: “If you want children you’d better get married.”’

Chung also suffered from Hepatitis C for 20 years, which left her in a great deal of pain, but was eventually cured, and more recently had a finger injury that kept her out of action for five years. She eventually made her initial comeback in 2010, playing the Brahms Concerto in Korea with Vladimir Ashkenazy and the Philharmonia. Her performance received such a great response that she played the last movement as an encore: ‘It was a wonderful feeling to be back on the stage.’ But she didn’t feel back to full health and rather than pursuing her solo career took a role next to her sister Myung Wha Chung as artistic directors at the Great Mountains Music Festival in PyeongChang: ‘It’s fabulous there, music making with all generations including young kids.’

‘It doesn’t seem possible that young players can be so technically flawless. In the 60s the level was only impressive in talented pupils’

What does she think of the young generation of players? ‘Technically they’re so capable, as if they could continuously break world records in sports. It doesn’t seem possible that they can be so technically flawless. In the 60s the level was only impressive in talented pupils.’ She sees that they’re much more educated than her generation: ‘These days nobody even looks at your PhD because everyone has one. In my day it meant something. The quantity of education you have to digest now is far greater.’

And maybe this isn't such a good thing: ‘In order to have your personal character you need to invest time in yourself, away from all the pressure and bombardment. We have to give students a chance to develop their character, their sound, their fantasy. For me, the important thing is depth. Mechanical achievement is materialistic. I don’t work in five senses – I work in six. How is the young generation able to cope with the sixth sense, given what they’re supposed to do: so much repertoire to learn, so little time, so much pressure. They’ve got to win first prize and that’s their goal. When I’m coaching my students, I say, “You’re going out into society, into the world. What would make you happy?”’

‘I have so many students who don’t practise. They’re too clever. When you practise, you get better. That’s basic’

For many of her university level students, their answer to this is to play like her and to have her solo career, but she’s realistic with them. ‘If you want to perform you have to start when you’re very young, to be exposed to stage life and to be trained. But you play very well and this can apply to chamber music. Or you have to really examine yourself introspectively: how do you want to connect with this music and your voice? Your sound has to touch people. It’s not about going out there to win a prize.’ It also requires a lot of work. ‘First of all it requires commitment. You have to be diligent and to do your part, which means practise, work. Without that you can’t complain. I have so many students who don’t practise. They’re too clever. When you practise, you get better. That’s basic.’

‘Players are so preoccupied with playing the whole piece without mistakes that they have no identity’

The theme of self-discovery is a recurring one in Chung's advice to her students: ‘Go for what you can do very well. Find your strong point, know it and have authority over what you can do. All the rest comes with you. When I have a pupil going for an audition I say, “Your first note has to make it. The first few minutes, a minute, even 30 seconds, are long enough to convince the jury that you’re amazing. Usually when people hear the first bar they know if it’s impressive.” But players are so preoccupied with playing the whole piece without mistakes that they have no identity. I train students to play with the conviction that they can do it, that they’re the best. I had this too. My mother and sister would say, “You’re the best, go out and do it.” So I’d say, “Okay, I’m the best.” If my mother didn’t make a comment then I knew it wasn’t particularly interesting. When I played the violin well she would say, “Oh, you’re making me cry,” so always I wondered if my playing was making her cry.’

At the time I speak to her, the finals of the Indianapolis competition are in progress, with five out of the six finalists Korean, prompting some online discussion about this emerging cultural supremacy, including a certain amount of stereotyping of Koreans having technique but no artistry. She vehemently contradicts this: ‘We are artistically very gifted. Throughout history you can see how original Koreans are. China is on a big scale, but as a neighbouring grand empire it never managed to dominate Korea, so we were left to develop on our own. Korean people come from a small country and they need to find a space to live, so they want to go as far as they can, as quickly as they can to find better choices. They are very artistic and one of the hardest working people.’

‘It’s always been like that. They need to sell the products; otherwise the world doesn’t go round’

Does she think the classical music industry is more focused on youth and beauty than when she started out? ‘It hasn’t changed a bit. It’s always been like that. They need to sell the products; otherwise the world doesn’t go round. What has changed is the phenomenal explosion in communication and the development of software. It’s happened so fast and people have an uncanny ability to follow the change. But it is difficult to correspond that with actual art.’ So she doesn’t feel all this digital communication threatens classical music: ‘Even if classical music is in the minority, people know they need and value it so there will always be people working towards it. There are a lot of negative people who say it’s dying, but I’m far more optimistic.’

Chung seems to be a natural optimist, maybe buoyed by her strong religious faith, and is philosophical about the ups and downs of her life. ‘I’ve been through all sorts of trial and error. Everyone goes through incredible difficulties in life just trying to figure it out. Life is a single journey and one’s path is never applicable to anyone else. You have to be happy with yourself. It takes tremendous reflection to learn that happiness is in your hands. You have it in front of you if you know what to look for.’

Does this life journey show in her playing? ‘You’re born with certain rhythm, a certain character that never goes away, but experience gives you a completely different perspective. What seemed so important at a certain time of my life I’m not even conscious of any more.’ I’m sure I’m not the only one looking forward to hearing this personality and perspective once again live on stage.