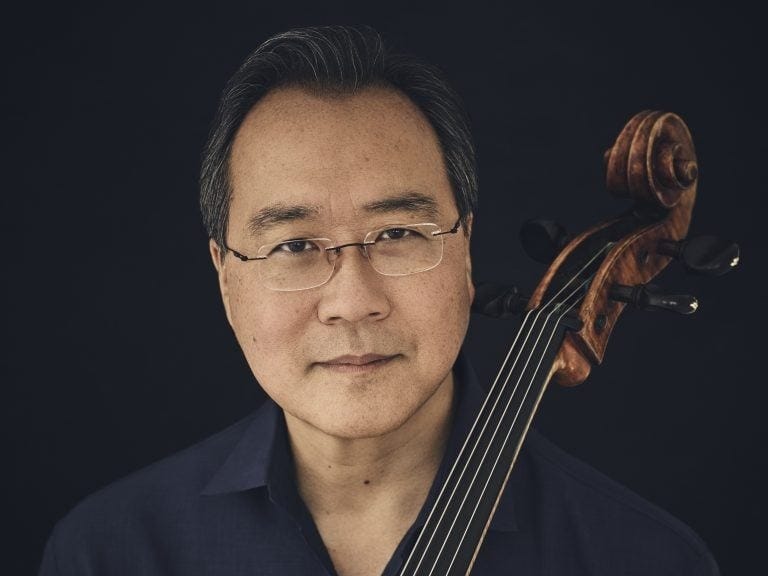

The Freewheelin’ Yo-Yo Ma

ARCHIVE As visionary cellist Yo-Yo Ma prepares to take to the stage at Royal Albert Hall for piano trios with Leonidas Kavakos and Emmanuel Ax, I revisit a thought-provoking interview he gave me

As I head out the door to see the stellar trio match of Yo-Yo Ma, Leonidas Kavakos and Emmanuel Ax at the BBC Proms, I thought I’d post an interview I did with Ma in for The Strad in 2011. At that point his Goat Rodeo CD with mandolin player Chris Thile and bass player Edgar Meyer had just come out, but typically for his lateral-thinking mindset, the conversation ranged far and wide over many of his other passions

Yo-Yo Ma tells me he’s no good at improvising: ‘It’s not my strength’. But I don’t believe him. Interviewing him, even long-distance by phone, his conversation is more freestyle extemporisation than conventional question and answer. Sentences lead into one another without quite finishing. Thoughts flow into other thoughts, emerging as philosophy, and then come back round to their starting point. There are occasional flashes of self-deprecating humour, a few arresting non-sequiturs and plenty of rhetorical questions. And at the end of every solo the question is thrown back to the questioner with impeccable musical manners.

In truth, I don’t always understand his meaning (I lie whenever he asks me, ‘Does that make sense?’) but at a deeper level, everything makes sense and connects with Ma’s world view. Ma is the ultimate holistic musician. Everything he says or does manifests his deep resolve to find connections – between disciplines, people, philosophies, cultures, genres. A quick glance at his back catalogue provides physical evidence of this, musically – over 75 CDs range from the obvious cello warhorses and classical chamber collaborations to his multicultural Silk Road Project, and work with the likes of Bobby McFerrin. He even recorded a Christmas holiday album, Songs of Joy and Peace, with musicians such as Dave Brubeck, James Taylor and Diana Krall. Nor can anyone accuse him of being populist – in August he delivered the world premiere of Graham Fitkin’s Cello Concerto to the BBC Proms audience with utter conviction.

‘It’s four people who really want to collaborate together and who’ve been brought together through friendship and mutual respect’

The latest in this distinguished recorded output is the Goat Rodeo Sessions CD, a coming-together with friend and former collaborator bassist Edgar Meyer, fiddler Stuart Duncan and mandolinist Chris Thile. The title refers to the term aviation people use about a high-risk situation in which many different things have to go right in order for everyone to walk away safely. For instance, four such musicians, at the top of their respective fields, finding time to come together to record an album. For Ma, the name was also to intrigue people: ‘We wanted a title that doesn’t make people think “I know what it is” but more “What is it?” It’s four people who really want to collaborate together and who’ve been brought together through friendship and mutual respect. The spirit of trying to be able to have one voice as a band is strong and yet everyone has individual voices. In essence it is all the values of what we would like to think a string quartet does.’

Ma describes the style as ‘aggressive bluegrass’, but to my ears that undersells its scope and imagination. The music is by turns folky, sweet, driven, lyrical, funky, tender, intimate, show-off and sometimes even a little strange. All the while, the five voices (with occasional bit parts from others) work perfectly together, just as Ma describes – distinct but complementary, and each one is delivered with brilliance. Ma’s role is usually the mellow lyrical material that binds it all together, although in a couple of tracks he lets rip with rhythmic motifs.

The project came about through his friendship with Meyer, a fellow traveller with whom Ma has recorded Schubert’s ‘Trout’ Quintet and who has been part of the Silk Road Project and Ma’s recordings of Apalachian music. Meyer introduced Ma to Thile, the boy wonder of the mandolin. ‘Edgar wrote me a letter seven years ago saying I had to meet Chris Thile. Being the way I am it took a number of years before we met and we worked together for my Holiday album. He did something so extraordinary and I saw exactly what Edgar said were Chris’s attributes – he’s a fearless boy wonder with an energy that knows no boundaries. There’s no impediment between his very fertile imagination, his curiosity and love of life and its translation into the mechanics of playing. There’s no resistance between thought and production. I find myself first marvelling and smiling, and then shaking my head and wanting to tell somebody else about it.’

Ma was happy to take a back seat in the creation of arrangements, leaving that to the other three and working off the written score. He explains: ‘I don’t spend a lot of time thinking improv so I don’t feel I should necessarily do it or need to do it.‘ He describes the rehearsal dynamic: ‘Things change as we rehearse so there’s a very fluid group dynamic. I don’t think it’s the traditional “I write, you play”. It’s “let’s hear all the things we’ve done”. The CD was recorded over a few sessions, with the players sitting in a circle in the studio facing each other, and without the use of overdubs, adding to the live thrill of the end product.

Ma is by now used to working with musicians of different styles, but what does it feel like to be the classical interloper? ‘I’m not a member of that community – I’m a guest. They’re letting me into their culture and their community and their 40 years of history.’ Ever one to find similarities among difference, he explains: ‘In classical music we have stories about what Barbirolli or Klemperer or Heifetz said. We all know the one where someone says “Great violin”, and Heifetz replies, “I don’t hear it”. And they have their stories, when people said ridiculous things, or about so-and-so who thinks they’re Bill Monroe. I’m taking this in and then reinterpreting it into the parallels I know.’

The word ‘community’ comes up a lot in a conversation with the cellist, in various contexts. In terms of the classical music community, Ma is king. He’s one of the very few 50-something string players with an international solo career these days. He is bankable, one of only five names that are guaranteed to sell out venues these days, according to recent comments in the Washington Post made by classical music promoters Anne McKay and Welz Kaufmann (the others being Itzhak Perlman, Joshua Bell, Lang Lang and Renee Fleming).

‘All the creativity that’s happened in any tradition has resulted from people who are at the edge’

And yet many of the recordings he has made in recent years have been as what he humbly describes himself as ‘guest’ in other communities. This is not unheard of (his fellow top-fivers Perlman and Bell have explored klezmer and Indian music respectively) but for Ma it’s been more consistent, and insistent. It’s also very zeitgeist, chiming with an apparent opening-up of musical genres among the generations who have their MP3 players on random play, accessing classical, rock, folk, world music willy-nilly. Ma doesn’t see this as a new phenomenon, though: ‘All the creativity that’s happened in any tradition has resulted from people who are at the edge. Look at Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and the sources he draws from. Or the Bach Suites and all the different dance movements from North Africa on to France and Italy. When we look more deeply into anything we find elements of whatever access people had to world culture.’

And the great artists from whom Ma takes his inspiration weren’t just looking into the neighbouring musical forms, according to Ma. He finds inspiration from the ones who were into every possible discipline of the times they lived in. For him, a musician must be more than a musician. He asks (rhetorically): ‘So you want to be a soloist? What does that mean for our era? What did it mean for Liszt, Mozart, Paganini, Joachim?’ He answers (his refrain building in rhythm and intensity): ‘They were composers, they were multi-instrumentalists, they liked folk music, they were great improvisers, they were great citizens, they were literary critics, they studied medicine, and they were incredibly generous.’ And then he concludes with his philosophy: ‘You only need to go to the next step of whatever you think is worth pursuing, but if you want to pursue it deeply you’ve got to know the world.’

I raise a pragmatic note – what does this mean in practical terms – and his invention takes off: ‘Let’s break it down to the level of job creation. What creates jobs? At the most basic level there’s no society that doesn’t have music. What is the function of music? It makes things memorable. People who hear music at a certain age always remember it at a certain time. People who are suffering from dementia or Parkinson’s Disease can respond to music. There’s an element of music that can get through to people who are in a coma. Music is shared among teenagers as one way of identifying who they are. So the community thing is necessary. Music goes very deep into people’s limbic systems. If you look at it from that point of view and build it up from those needs you can say, “I’m 15 and I play the violin. I can go to music college, I can go to university, I can get a degree, I can do all kinds of things”. And, my god, you have a job. If you’re an artistic, creative person you decide that the greatest thing you can do with your life is to make your life an artistic enterprise. You create your life. You follow your interests and you find the right place for all those interests, so you’re using all of yourself. But you’re never doing it as just a job. You’re giving of yourself, of all of your substance, to anything you focus on.’ See what I mean by holistic?

‘There are so many pathways. For everything there’s a traditional pathway that has worked for 40, 50 or 60 years, but our environment has changed dramatically over the last 30 years’

He reiterates and extends the theme, inventing a whole lifeline for me as he speaks: ‘So if you incorporate all of that, you could say, “I’m 15, I can make a group with my friends, I can join things that are appealing to me, I can participate in older organisations that work in a certain way because that’s fun. I like to play the Sibelius Concerto so maybe I’ll join the Sibelius Society and we decide that I’m going to play the Sibelius Concerto, but I’ll also enter concerto competitions and maybe that’ll be where I have a different proportion of my life playing the Sibelius. But on the other hand, I’m really interested in Baroque music and digging in libraries, looking for music that hasn’t been played before. And I bring my friends to form a quartet in a neighbourhood storefront in a different part of town. Maybe as I get older I’ll have a partner and we have some kids. I’ve adopted some kids and I think there’s a need for children’s theatre, so I’ve joined with some of my friends who have kids and we’ve joined with a theatre group to do these things for groups of 70 people and suddenly that takes off and we go to six communities because all these over-anxious parents want to give their kids a rich imaginative life.” And suddenly you find you’re playing fewer Sibelius concertos and more of that. There are so many pathways. For everything there’s a traditional pathway that has worked for 40, 50 or 60 years, but our environment has changed dramatically over the last 30 years with the internet and all the new knowledge. If we had a stroke our brain would be creating new pathways. How do we create new pathways?’

The examples that Ma has described don’t actually come from the depths of his imagination, though. They’re real examples of work that is being done as part of the Citizen Musicians project, his money-where-your-mouth-is brainchild. In 2010 he took up the position of creative consultant for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) and has since been working with the orchestra and its music director Ricardo Muti to harness the collective powers of local musicians towards the benefit of their communities. This takes the form of players going into schools, hospitals and detention centres – with Ma a fully participating representative. He describes what they do: ‘The first thing Riccardo Muti did was to go into Warrenville, a young person’s detention centre, working with people to develop their own music and songs. I’ve gone in a couple of times to be the music for the songs that they’ve written. It was very moving. It’s a humanising thing. There’s a five year old with leukaemia and we went into the children’s hospital as part of a weekly event.’

‘We need to do the positive thing of saying that one of the musical values we all treasure is that we work towards something that is bigger than ourselves’

It’s not hard to see how the work fits with Ma’s philosophy of life: ‘We have enough examples of our world about non-collaborating – whether they’re political organisations or countries or sects – that I think we need to do the positive thing of saying that one of the musical values we all treasure is that we work towards something that is bigger than ourselves. So in every action I take as a musician or a human being, am I working just for my own interests or am I working for something that’s bigger than myself?’

This can’t only be all about morality, though – no orchestra can survive on integrity alone these days, and for Ma the project does tie in with a bigger picture of funding. ‘We’re just trying to say, “Here are a lot of different possibilities”. One of the biggest problems that all arts organisations have is the feeling of, “What about us, what about our funding?” Unless we take the view that we’re not participating in a limited slice of the pie, but that we’re actually participating in recipes for as many pies as we want, then we’re not doing good cultural work. Because culture should be about the largest possible examination of human interaction and expression.’ He asks, ‘Does that make sense?’ I’m not sure, but I think he means that arts organisations don’t necessarily have to be in competition with each other, and that if they all go out and generate more audiences by what they do, then artistic and business goals can be met, although it’s hard to pin Ma down to such mundane realities as ‘generating more audiences’.

‘There’s a need for reconvergence, which is actually happening because more fields are now being created that are interdisciplinary’

Is it practical, I wonder, ever trying to bring his buoyant optimism down to earth to see if it can survive there. ‘It’s realistic because I’m trying to define it differently. I’m trying to say, let’s look at our work not as an economically imposed thing. If as cultural workers we work in the currency of imagination, if we can match that imagination with needs that are not yet apparent in the real world, we can create the preconditions for new jobs to exist.’ He struggles to articulate the complexity of his thoughts: ‘I’m trying to put it into words in my own head so I can understand why I’m doing what I’m doing. How do we do it in our era and what words and terminology do we need to construct a vocabulary that is resonant with practitioners? Arts and science used to be part of philosophy. Then we had to construct new fields of science within science, and they got separated. It’s a little Tower of Babel-like. There’s a need for reconvergence, which is actually happening because more fields are now being created that are interdisciplinary.’

The concept of the Tower of Babel is a useful one for understanding Ma’s world view: lots of people running around the world talking different languages when fundamentally they all have the same capacities and needs that were once described in a unified language. His mission is to get everyone talking together about the the things that matter, whatever their perspective is – reconverging. And while that sounds impossibly highbrow and philosophical, he is busy articulating it through the best way he knows how – music.

So it’s not hard to see why he prefers not to improvise. When he talks he sees so many directions in which the conversation can go at any one juncture that his tongue literally can’t keep up with his brain. There are so many levels to his thoughts that he sometimes has difficulty working out which one to discuss. And maybe it would be the same for him improvising. But judging by his conversation, that doesn’t mean he wouldn’t be any good at it.