Very sad news has come through that the great violin pedagogue Sheila Nelson died on 16 November, at the age of 84. By rights, Sheila would have spent her final years basking in the affection and gratitude of the many generations of professional and amateur musicians who were inspired by her. She would have toured the country dispensing wisdom about classroom string teaching for the organisations that are now attempting to solve the problems she’d resolved brilliantly decades ago. Governmental departments would have come to her to understand the importance of lifelong musical well-being. She would have been honoured officially around the world for the significant contribution she made to string pedagogy.

As it was, she had Alzheimer’s Disease and spent the last seven years being looked after by her family, cruelly robbed of these satisfactions. Not that she would have had much truck with them – she was far too self-effacing and no-nonsense.

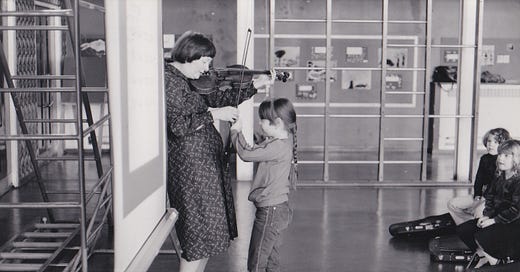

I am one of the lucky ones who had Sheila as my first teacher. I wrote here about the Saturday mornings spent in her large house in Cromwell Avenue, crowding in for the fun and games of learning to play the violin, both individually and in groups. In the early years, it was mostly about fun – comedy props designed to position little hands properly, silly analogies involving animals, a Stetson hat to select the next child required to improvise, physical activity to encourage relaxation and good pulse, and lots of lots of circles in the air. Later on, there was serious chamber music crammed into every room of her house, and there were always performances, invariably ending with ice cream all round.

It’s over 40 years since I enjoyed these fun and games, and yet hardly a day goes by that I don’t feel grateful. I still play chamber music with the friends I made there when I was five, as well as many other amateur friends I’ve made along the way – it didn’t take Covid to prove to me how important playing the violin and music are in my life. I’ve never had tension problems in my playing and have always enjoyed improvising and playing concerts, unlike many musicians. Sheila’s great achievement was to make sure that music (classical music, at that) was always fun, joyful, physical, sociable, satisfying. It might not sound surprising, but it is not a given. Her way of teaching meant that playing the violin was not only something that little kids wanted to do – they didn’t want to stop doing it.

She did that for me and my middle-class friends whose parents were willing to drive up to Highgate twice a week. And she did it with as much passion – maybe more – for the less-privileged kids she taught through her pioneering Tower Hamlets String Teaching Project (you can read my mother’s article about that here). She had a truly democratic vision of music for being for everyone. That might seem self-evident to most of us, but it’s a legacy for which we have to fight harder than ever.

I got to meet Sheila again at the European String Teachers Association summer conference in 2010, when I was still Editor of The Strad. I sat with her at lunch, and when we were suddenly left on our own together, I managed to stumble out some inarticulate words of appreciation – how does one put that sort of sentiment? I don’t know how it came across or if she took them in properly, but I’m glad I had the chance to say something to her while she still had the capacity to understand. I just hope that one day soon her students and colleagues will all be able to celebrate the enormity of her impact on our lives.