Responsible adults

New generations of star players are committing to music education at the grass roots level with a focus that might create lasting change for classical music

There’s not much good news in the classical music world at the moment – it’s mainly devastation, uncertainty and fear. But one positive trend offers a glimmer of long-term hope. In the last few weeks there’s been plenty of evidence of how the younger generations of soloists are embracing their social responsibilities, committing to music education in thoughtful, creative ways, leading me to feel genuinely optimistic.

Leading the charge with conviction and intellect is Nicola Benedetti. She and colleagues from her eponymous foundation recently provided two weeks of free online string workshops for anyone who was interested, whether young, old, professional or amateur. They reached 7,000 people in 66 different countries, and the hour-long final celebration was an emotional testament to the power of music, hard work and connection, even via Zoom.

Jess Gillam’s first Virtual Scratch Orchestra brought together 934 musicians from 26 countries aged 6 to 81, to play Where Are We Now?, and their second track is on its way. During a conversation organised by Orchestras Live, she explained that one of her take-outs from the current crisis is a commitment to incorporate educational work in local schools whenever she goes on tour. She already has form, as a trustee of HarrisonParrott’s Foundation and working with organisations such as National Children’s Orchestra.

We also saw a host of young soloists, including Sheku and Isata Kanneh-Mason, Ben Beilman, Benjamin Baker and Elena Urioste, play Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star with a group of young students from London Music Masters, which serves children from mixed cultural and social backgrounds across London. Since lockdown the organisation has continued an impressive online offering and has even opened up its teacher training programme for free.

London Music Masters pioneered the concept of bringing in such soloists to work with children from its foundation in 2008, developing a complete eco-system with kids, teachers and soloists working together and learning from each other. Children have music in their lives, teachers develop best practice and young soloists learn to communicate and inspire little ones. It’s a win-win-win.

‘What we’re seeing here is a commitment by young players at the grass roots level, to children who may or may not be talented and may or may not become professionals’

Of course, famous soloists have often given masterclasses and held teaching positions. Yehudi Menuhin even started his own school. But this usually happen happens at a certain age, once touring and practice become tedious. It’s often expensive and superficial – a quick visit to a conservatoire to dish out advice to the cream of the students. What we’re seeing here is a commitment by young players at the grass roots level, to children who may or may not be talented and may or may not become professionals. It doesn’t matter – they can all enjoy it and benefit from it. With such enthusiastic mentors they may even realise that classical music is cool and exciting. At a time when music has been stripped from the syllabus and there are all sorts of calumnies about it being elitist, having such champions couldn’t be more important.

This cause may have been accelerated by lockdown, in that soloists are sitting at home with time on their hands, unlikely to resume international tours for a while, but it also speaks of a generation that takes its social responsibilities seriously and sees the big picture. It might also be a smart development in a dysfunctional music business where artists earn peanuts for recordings and now that concerts are all but dead until 2021. I don’t begrudge any musician who finds new income streams, as long as it’s done with integrity and thought (education work won’t make anyone rich, anyway).

‘Music students are generally not encouraged to teach and are even put off from spending time learning the craft by their own professors’

It also flies in the face of an odd paradox of classical music whereby music pedagogy is devalued by the very industry which entirely depends on it. Music students are generally not encouraged to teach and are even put off from spending time learning the craft by their own professors. (This attitude may also be changing with younger generations of professors.) Conservatoires pay lip service in offering specialist courses, but there still seem to be silos for those who are likely to become teachers, while ‘soloists’ are left to practise their six hours a day and play in all the conservatoire orchestras. In reality most of them end up teaching, but have to make it up as they go along.

I’ve never understood the logic of this. A strength of the old Russian school was that students taught from early on – one of the reasons its traditions are so thorough and successful. Being able to teach others and therefore themselves allows musicians to develop throughout their lives. These young artists are reclaiming teaching as a vital element of being a musician – it empowers them as well as their students.

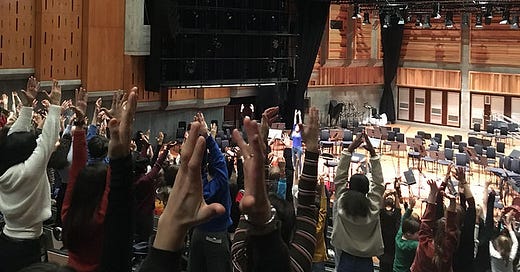

That’s not to say that they should be teaching the nuts and bolts of playing an instrument. It’s not right for star musicians to come in and threaten the livelihoods of teachers. One of the key things about Benedetti’s sessions is that they are supplementary to students’ own lessons. When I watched her in action earlier this year leading a session at the Royal Festival Hall, she obviously knows the pedagogy in depth and explains it as necessary, but her role is largely to inspire and galvanise both students and teachers. One of the aims of her foundation, and of London Music Masters, is to support and enthuse teachers and raise the level of teaching, rather than undermining or replacing them.

‘They might have long and happy careers rather than burning out in their 40s or being destroyed by the physical demands of relentless performance’

Will these players have less time to practise, less focus to study their scores and less drive to perform concertos around the world? Possibly. But they might also connect better with the innate joy of music, discover new ways of learning, find new stories to tell and derive real satisfaction from the change they’re seeing up close. They might have long and happy careers rather than burning out in their 40s or being harmed by the physical demands of relentless performance. (And in truth, the things that bug me about playing today relate to style and personality rather than technical perfection, but that’s for another article.)

Most importantly, these players are encouraging the audiences and players of the future and ensuring that classical music is as inclusive as it can and should be. Despite the catastrophic possibilities of our present situation, there are opportunities to rebuild our world and these musicians are offering us all a better future. Long may they continue.