I ❤️ Beethoven

For the first stop of my Interrail trip, I make a beeline for Beethoven’s home city of Bonn and find him around every corner

I love Beethoven. I hate kitsch. I’m pretty sure that Beethoven would have despised kitsch (the tinky-tonk bit in the Ninth Symphony notwithstanding). And yet I love Beethoven kitsch. Somehow, in this syllogism, I am reduced to absurdio.

And so, for the first stop on my coming Interrail jaunt, which was precipitated by an impulsive buy in the train company’s half-price sale last year, I find myself taking five trains to get from London to Bonn, the birthplace of the iconic kitsch-whisperer.

I arrive in the evening and go for a leisurely walk beside the relaxed Rhine, along which, a helpful sign explains, Beethoven sailed for his first public concert in Cologne in 1778. I walk past MS Beethoven, which offers river cruises, and pass the Beethoven School, a Beethoven car park sign, a Konditorei selling Beethoven chocolate and a sculpture that takes the claim that Beethoven was ugly rather too literally. I arrive at my hotel to find a display of his scores in the entrance. At every corner of this pretty-if-uninspiring city, images of the famous head loom, pop and sell. And I am absolutely here for it.

Actually, I’m here to see the Beethoven-Haus, where he was born in December 1770. I’m at the front of the queue for tickets when the booth opens at 10am, and I am not disappointed. Three floors of one of the city’s few original unscathed houses display paintings and cases holding objects, manuscripts and letters. An accompanying app audio tour goes into more detail and offers useful context. There’s not an overload of musicological or historic detail, but it’s a good balance between being general enough for average tourists and detailed enough for nerds.

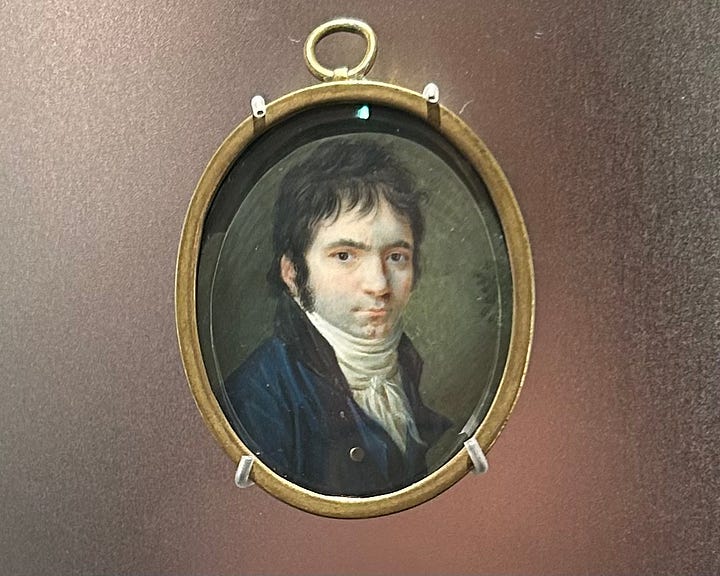

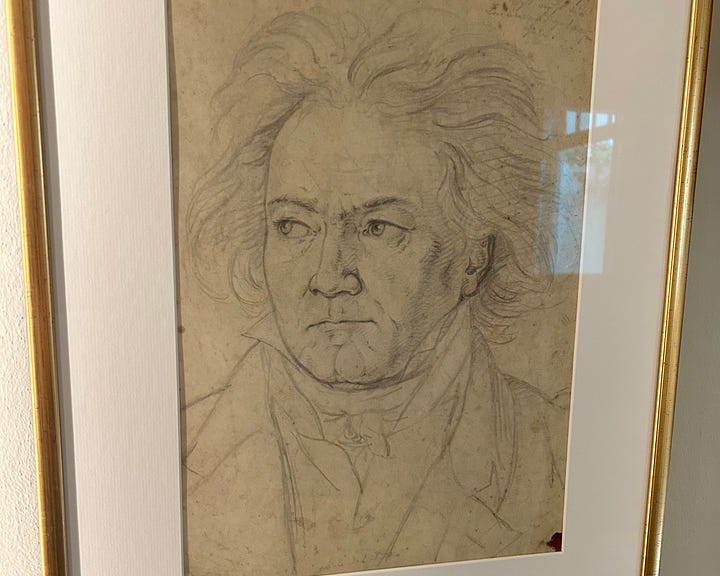

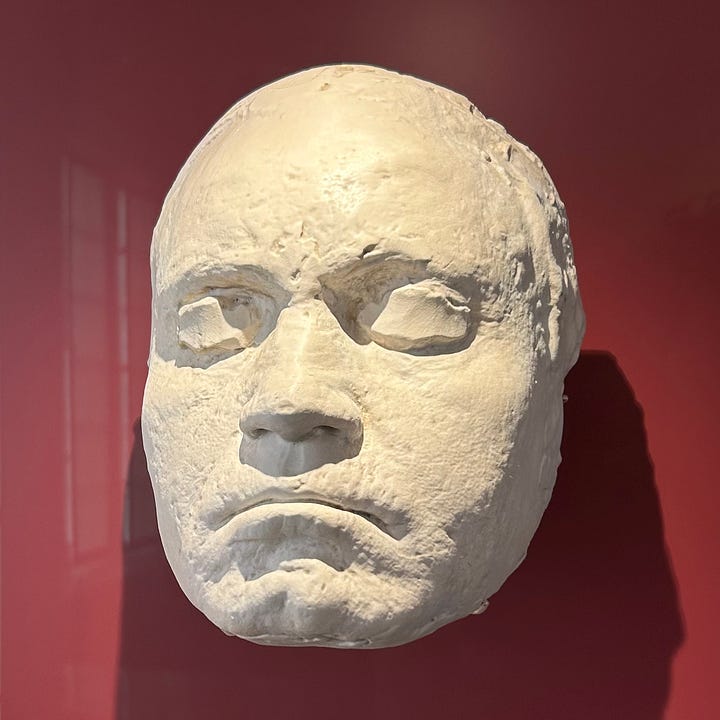

For me, it’s enough just to be in a space that he once occupied and breathed within, even if it was only one of several of his family’s homes before he left the city for good at the age of 21. My imagination does the rest – picturing him being bullied by his father, carrying his viola to rehearsals, scribbling his scores, monitoring his housekeepers’ budgets. It’s enough just to stare at the various portraits of him in the first room and envisage them alive. A mask made when he was alive is especially vivid, showing all his pock marks and his scarred chin, as well as his miserable expression. (The guide points out that the process of making the mask would have been fairly unbearable, so it's possible that affected the facial expression that has defined our popular conception of him as a grumpy old man).

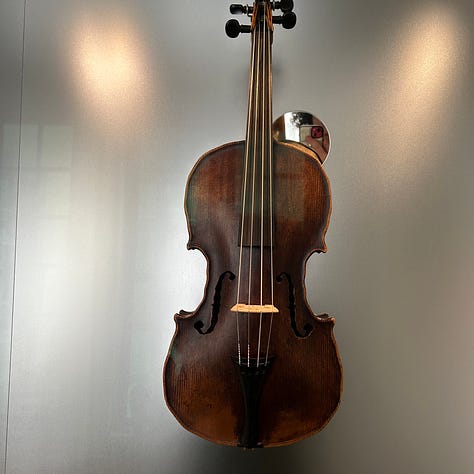

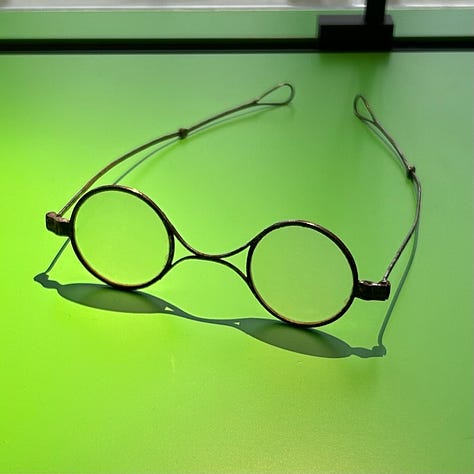

The letters are mainly facsimiles, as the originals are presumably too fragile, which is understandable, although lessens the impact on the imagination somewhat. For me, it’s the thought of him actually touching something that brings him to life. Fortunately, many of the objects are the real deal, including his eyeglasses, the last quill he used, and various musical instruments, such as the viola he played in Bonn’s court orchestra, and the complete quartet he was given by Prince Lichnowsky, which he refers to in his Heiligenstadt Testament. There’s also a photograph of his nephew, in whom you can recognise the cleft chin, which is rather moving, given the nature of their fractured relationship.

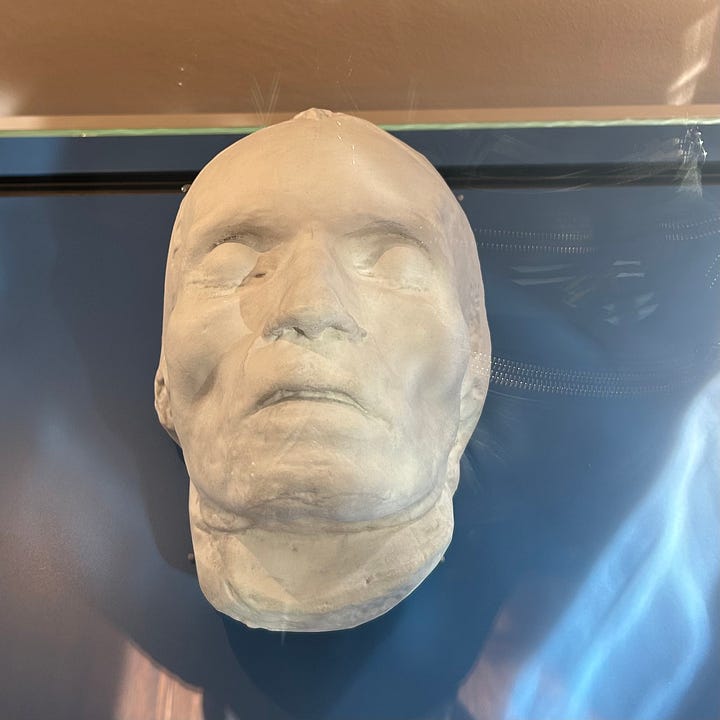

By the time we get to the second floor the theme is ‘The Blows of Fate’ and we hear accounts of a treatment that involved having bark rubbed into his arms, causing blisters, and his frustration at not being able to use his arms for days – although it seemed to work. We see the surprisingly large hearing aids that were designed for him by Johann Mälzer, who also designed his metronome. His death mask is well known, but still has the power to shock and move.

I certainly learnt some new things – including that he wore glasses, had incredibly messy writing that would entertain a graphologist, and kept a tight rein on his staff. His idea of a working day seems pretty inspirational: an early breakfast, followed by some work; a walk; correspondence; lunch at a coffee house; another longer walk; and an evening spent in an inn or at a concert.

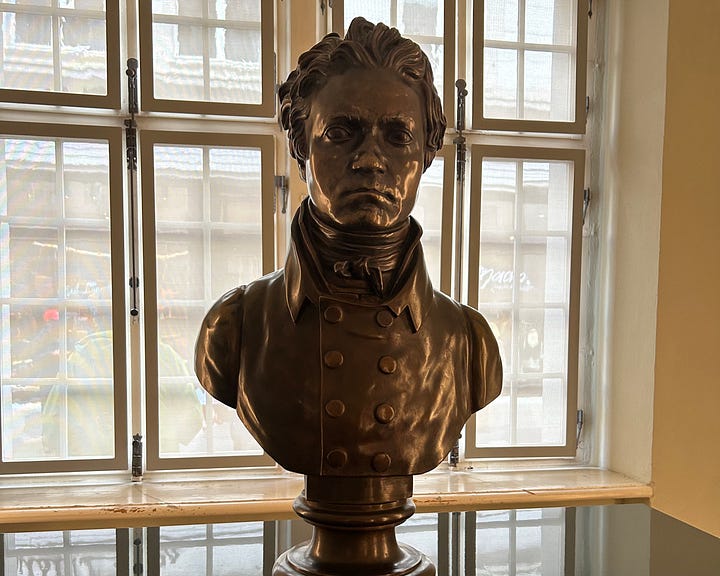

As I drank my apfelsaft in front of his imposing statue in the main square, I tried to imagine what he’d have thought of the gold statue atop a bar across the square and all the garish versions of him about a town that is cashing in, albeit relatively tastefully, on his name. One of the points the exhibition made was that he was an acute businessman, so maybe he’d approve of the commercialism and try to get his cut. He certainly didn’t lack self-worth, so maybe he’d lap up the attention.

Of course, it’s not really the kitsch that I love. It’s what it represents, which is that a composer and his music are so popular and well loved that they have transcended the usual boundaries and exclusions of classical music to sell bread and shirts. If he can do it, then it is possible.

As for me, in the act of thinking and imagining him, I feel he has become more present to me, and I will wear my favourite Beethoven t-shirt with pride, although, reader, I did not buy any Beethoven chocolate. Next stop: Leipzig. Bach and Mendelssohn, here I come!