Human imperfection will save us

Artificial intelligence impersonations of human writing are very good – and that’s why this writer isn’t afraid of them

There’s lots of talk these days about ChatGPT and whether Artificial Intelligence will replace writers. Like many of my journalist colleagues, I’ve tinkered with it. Its various answers to the question ‘what is the future of classical music writing?’ are not actually that off-kilter (see below). On the other hand, it variously describes me as a cellist, founder of Sounds Like Now, editor of Primephonic, jury member of Young Musician of the Year and ‘known for her insightful writing on classical music and her expertise in the field’, so what does it know?

Am I frightened for my career? Well of course in the days of nihilistic cost-cutting bean-counters, we should all be worried. On the other hand, of all industries, the creative ones know the value of humanity – of having a real, flawed human brain at the drawing board. That’s their whole point, after all.

The answers the ChatGPT generates are impressive in their content, synthesised from real writer’s ideas and words, and it’s all perfectly well written. And that’s the problem with it, because humans don’t write perfectly well. We all have our quirks and tics, and that’s what makes writing interesting.

Back in the day, I used to edit The Strad’s CD review section and would commission 30 or so reviews from a wide pool of writers. I could invariably identify each reviewer’s work without seeing their name. They each had their own idiosyncrasies – whether it was their use of specific adverbs or adjectives, their over-enthusiasm or under-enthusiasm, a reliance on historic context to fill the word count, a fixation on vibrato, their choice of Oxford commas or not, how they reacted to new music, how they liked to generate lists etc etc.

When I first took it on as a green editor, I scrupulously ironed these all out, deleting all the extremities and specificities that stood out. No doubt the writers would get their proofs back (yes, we had time to send them out in those days) and not recognise their own words. As time went by, I realised how wrong I was and learnt to be more laissez-faire.

Of course, there has to be a certain consistency in a publication, to which end a house style is essential, but maybe it is exactly the individual characteristics that make writing compelling, and the differences between them that keep readers’ attention and loyalty. The ChatGTP style is all smooth consistency and no character – bland, bland, bland. Now when I edit interviews, I cherish scrupulously the words and phrases that stand out and observe respectfully the nuances of a speaker’s tone.

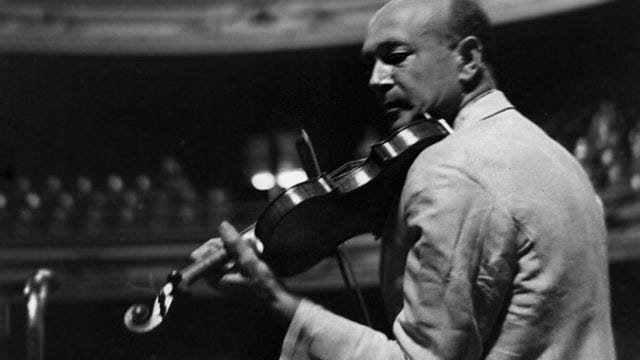

In all art, there is a precarious balance between consistency and technical perfection on one hand and uniqueness and creative freedom on the other. I’ve always been the first to whinge if a violinist plays out of tune or I don’t like their vibrato, and yet these days, I would much rather listen, for example, to Joseph Szigeti, for all his wobbling and shaking as he got older, than some technically perfect, sonically pure rendition. His humanity and personality speak to me beyond any flaws in his violin playing. I am grateful for this change in perspective, which is undoubtedly one of the benefits of ageing.

Charlie Chaplin was a notorious perfectionist, retaking scenes hundreds of times sometimes, but he was keenly sensitive to the importance of the bigger picture. In an interview in 1921 he explained: ‘I want every bit rehearsed thoroughly, all the technical details worked out very carefully. Then, when all those bits of business have been gone through thoroughly, I say, “Now we’ll act it.” But I don’t want perfection of detail in the acting. I’d hate a picture that was perfect – it would seem machine made. I want the human touch, so that you love the picture for its imperfections.’

Art is defined by the human touch. I’ve recently been interviewing players of the Academy of Ancient Music for the CD booklets of their Mozart Piano Concerto project with Robert Levin, which they’re continuing after a 20-year hiatus. In my interview with violinist Bill Thorp, he described Levin coming back to the project after all these years, saying, ‘He played with all the fluency, facility and inventiveness that he always has done, but there was an added dimension that made it even more moving. Maybe one’s life experiences go into one’s playing, so it’s not surprising that with age and experience there’s more depth. Just as old instruments sound better because of their age, players can move you more as they get older, because they can say more. I find Bob’s playing even more touching now. What is music, after all? It’s about life, experience and emotion.’

To illustrate the latest release, the AAM have commissioned an animation from André Beukes that also rather beautifully demonstrates the point. At the start, we see a young Robert Levin at the keyboard, playing the slow movement of K467, one of Mozart’s most sublime movements. As time and music pass, the supposed camera pans round him and an older man emerges, slightly more hunched and careworn, but just as intent on his work.

The film is made of 1,500 drawings – some descriptive and clear; some messy splodges and abstract colour washes that look like they took seconds. Our eyes piece them into a story that is both specific to the project, but also gets to the very heart of the matter. Life, music, humanity – full of splotches, voids, mess and inconsistency amid moments of extreme beauty. That’s the point, and ChatGPT will never get it.