Hello again, Bellowhead, my old friends

My favourite band was back in London Town with their unique brand of infectiously joyful music-making – and they did not disappoint

How many things in your life can you truly count on not to disappoint? Maybe not today or tomorrow, but eventually? Which great TV series doesn’t ultimately present a really duff season? Which actor doesn’t become a cliché of themselves? Even my favourite violinists have in time taken on annoying affectations or just become plain bored and boring.

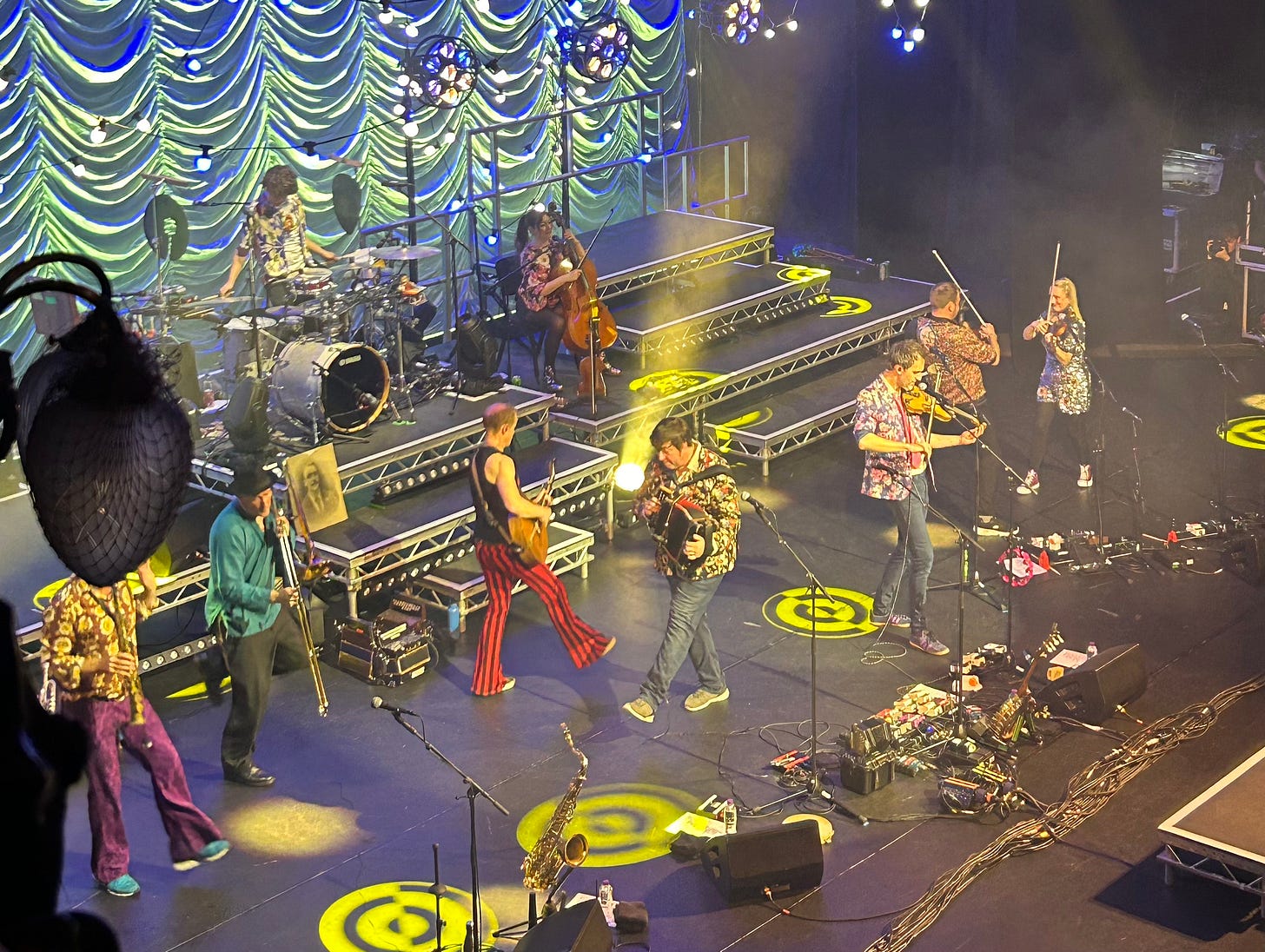

Step forwards Bellowhead: the least disappointing thing in my life. I fell in love with them nearly 20 years ago, and 17 gigs later, get exactly the same thrill seeing them live – the 17th being on Monday night at the London Palladium. The sheer rumbunctious energy of their chemistry, presence and musical arrangements is just as electrifying as the first times I saw them. They may all be a little older, with less hair or more girth, but then we all are. One of the many miracles of music is that none of that matters. Being a band groupie marks the passage of time and life, and yet simultaneously holds you in the moment you first fell in love. No wonder my favourite songs are still their earliest, including Prickle-Eye Bush and Across the Line (both of which they played on Monday).

Certainly, a scan of the Palladium audience showed a lot of white hair, so it seems we’ve all aged together, or maybe the demographics of London and ticket prices skewed it. (The folk scene doesn’t seem to have to worry about its white-skinned, white-haired audiences in a way that is demanded of classical music, but that’s another article). There wasn’t much dancing, and I felt for the band staring out at the seated crowd for much of the gig. The Palladium doesn’t lend itself to dancing, with ushers patrolling the gangways, which is a cruel handicap at a Bellowhead gig. Remembering this from their last gig there in 2016, I treated myself to a box, and was able to bounce around for most of the gig (although a little too fearful of the structure for full-on moshing).

Life’s tragedy is a constant presence alongside the joy, with the absence keenly felt of oboist and fiddler Paul Sartin, founding member and lynchpin of their sound and charisma, who died in 2022. They pay tribute to him before another favourite of mine – London Town. I wonder if musicians realise how large they loom in their audiences’ minds – I didn’t even know Paul but still feel the loss, so I can’t imagine how they must feel.

Bellowhead officially broke up in 2016, and even then, I was devastated, but not disappointed – I could understand why. One of the positives of the pandemic was that they reformed, first in an online gig and then with a tour last year. At the end of Monday’s concert frontman Jon Boden hinted at a future, so we’ll see how that pans out. It’s hard for any band to grow and develop creatively while maintaining quality and keeping everyone happy – audiences and band members alike. There are good examples of artists renewing their work with each new release – Bruce Springsteen, Paul McCartney and David Byrne, of my favourites – and I hope they find a way to move forward while remaining as addictively brilliant as they always have been.

I’m certainly taking no chances, though. One of the things I’ve learnt from being their groupie is to seize every opportunity to hear them, and to experience absolutely every moment of their live music. So I will be going to their Cambridge gig next week, armed with my latest Bellowhead T-shirt and dancing shoes. I’ll take my dose of Bellowhead joy wherever and whenever I can.

I republish below the blog I originally wrote in 2016 when they announced their break-up:

Bye Bye, Bellowhead

The ground-breaking English folk band has broken up after 12 years, leaving this fangirl sad – but grateful

I’m not a mosher. I don’t generally mosh. I’m more likely to be seen standing at the back of a gig venue, hands in pockets, listening carefully, judging warily and only jiggling my hips – a little self-consciously – if the music takes me. Maybe it’s something to do with my classical music background and a training in which every sound gets analysed, every phrase gets criticised and every structure gets deconstructed. Or maybe it’s because I have trust issues. I have to believe in something completely, both on logical grounds and through repeated experience, to really give myself to it and make a fool of myself for it. (Yes, I am single.)

Then I met Bellowhead, and all my self-consciousness and doubt went out the window. I became a full-on groupie and could be found at nearly all their London gigs, pogo-ing up and down near the front of the stage with a big grin on my face. Now they’ve toured their last tour, leapt their last leap, and sung their last song, and like so many other fans, no doubt, I’m feeling bereft.

It all started in September 2006, when my band, Los Desterrados, opened for John Spiers and Jon Boden at the much-lamented Spitz Club. I knew nothing of English folk music at the time beyond the clichés of beards, sandals, fingers in ears and monotonous voices. The duo, which at that time was starting to have success with Bellowhead, already gave me a new glimpse of the power of folk narratives and the range of sound and impulse of the melodeon and fiddle on their own. Intrigued, I went to my first Bellowhead gig in the Royal Opera House bar, in February 2007. The sound was dreadful, as you would imagine in what is basically a giant greenhouse. But even so, I caught the sense of energy and excitement of the band’s arrangements and performances. I bought their first two CDs – E.P.Onymous and Burlesque – and listened to them on repeat. I was hooked.

The moshing came surprisingly easily. From the beginning, the band was able to build up the energy of their gigs, pacing the audience with slow ballads leading to wild dance numbers. They got better and better, and at each gig you could see their stagecraft improving, particularly Jon Boden’s playing of the crowd, and the sheer wild sense of fun and subversion of the whole crew. There I would be – handbag contents carefully planned for minimum encumbrance – jumping a metre up and down in the air, in a complete trance, totally immersed in the moment. For all the soul-enhancing and tear-enducing moments I have had either playing or listening to classical music, none of them comes close to this sense of abandon.

Somehow, these ancient tales even managed to make me feel English, maybe for the first time ever. That may sound strange. But being first-generation English and culturally Jewish, with a mother who escaped Germany in 1938 and a father who fled South Africa, I always felt it difficult to identify as English. At home we listened to a mixture of classical music, Viennese schmaltz, jazz and classic musicals – the Beatles were about as English as it got. I’m grateful to this eclecticism now, but at the time it left me hopelessly out on a limb culturally, and having curly hair and a foreign-sounding name didn’t help. My family history was a dislocated one, and in many ways I was brought up more culturally German than English or Jewish, and yet none of them. The result was that I found it hard to say, ‘I’m English’.

But listening to the old English tales embedded in the Bellowhead songs, I felt I was assimilating the whole of English culture and history. The old narratives of love, death, taxation, drink, the sea, even prostitution, became my narratives (even though they were mostly male). Even the street names I passed located me at the centre of these stories: not by accident is one of my favourite songs London Town, whose hero ventures ‘up Cheapside’, where I worked at the time. One thing led to another and I listened to lots of other English folk musicians past and present, and started going to Cambridge Folk Festival. I went to a fiddle class run by Sam Sweeney and when I was Editor of The Strad I commissioned Jon Boden to write an article about the English fiddle tradition. This was now my tradition.

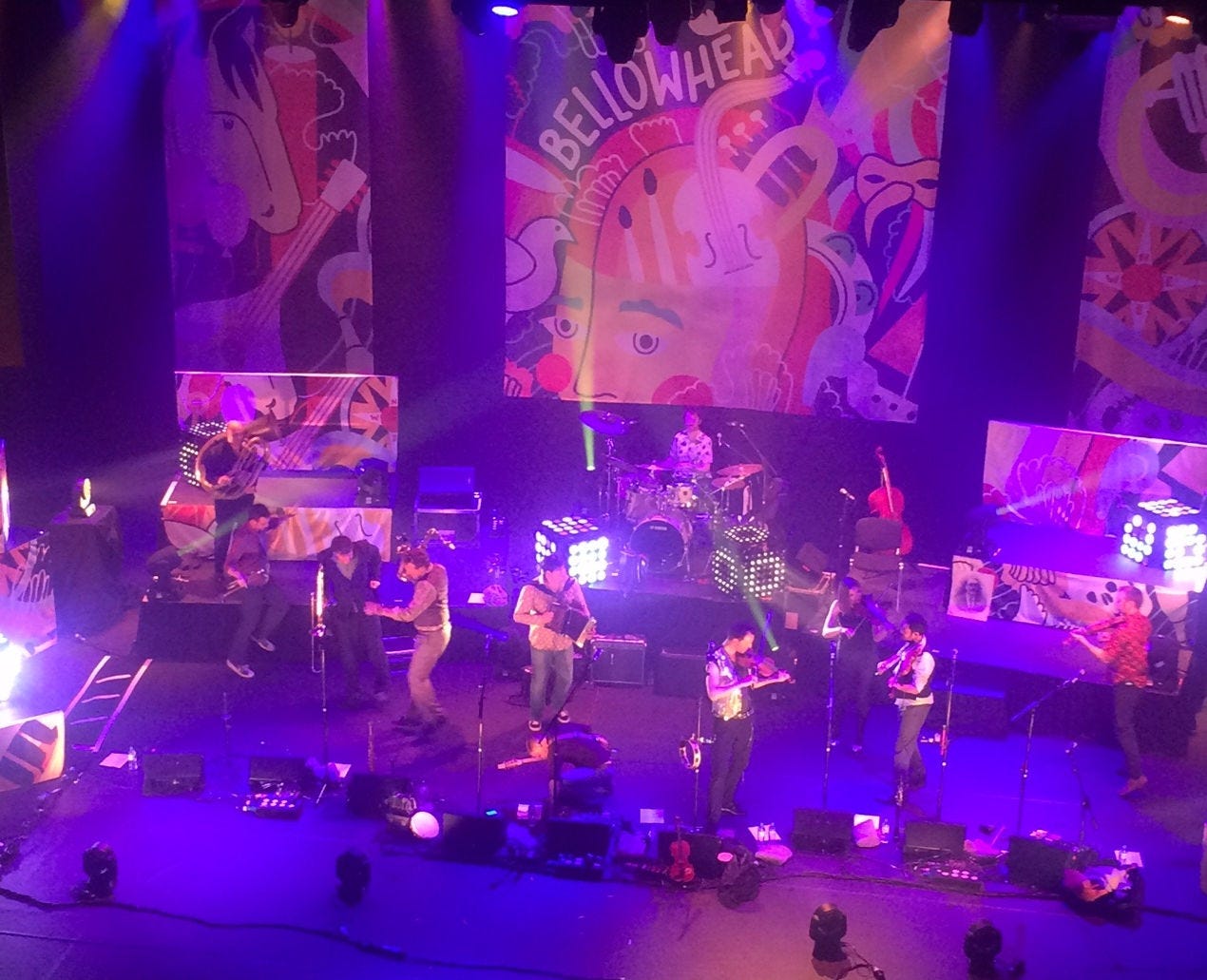

Not that I ever lost my sense of critical judgement. Part of the massive appeal of the songs was the sheer inventiveness, sophistication and intelligence of the arrangements, and I revelled in these. With eleven players, a bass section unusually made up of a helicon, trombone and a cello, blending with saxophone, trumpet, oboe and fiddles, among other instruments and random rhythmic devices, this was a new sonic world, more like an orchestra or big band than a folk group, and the arrangements exploited all the possibilities, both rhythmically and sonically. Each song had its own sound stamp, its own quirks, riffs and textures, but all were unified by the superb individual musicianship and a certain acerbic sense of humour – no doubt typically English. It was the ideal mixture of carefully crafted music with wildly danceable rhythms – Nietzsche’s perfect synthesis of Dionysian and Apollonian.

There were times when I judged harshly, though. There were a few albums in the middle that I thought were fussy and over-produced: too punky, poppy or clever. Inevitably the live gigs were better than the recordings, few of which captured the madcap energy. There was also a part of me that was a little jealous of the attention they were getting from the likes of Chris Evans on his radio show and the funny tour videos they put out – I didn’t want them to be too mainstream, and I scorned the bands who tried to copy them, with less of the talent and intelligence.

I could also identify with the artistic challenges they faced, as my band was having the same issues. In a parallel sort of way, we perform ancient Sephardic-Jewish songs with similar timeless narratives of love and death, which we arrange according to our own variety of musical sensibilities, and sing in Ladino. We’ve been going even longer than Bellowhead, since 2000, and the dilemmas are the same. How do you keep growing as individuals, developing the band sound in interesting ways, and making distinct albums, without going too far from what made you good in the first place and from what the audience wants to hear? And what if members want to express themselves by writing their own songs to add to the tried-and-tested historic canon? Thankfully, Bellowhead stuck to the old ones, although occasionally they threw in other classics – their version of Jacques Brel’s Amsterdam is a masterpiece of musical tension-building. (And they did do some wild cover versions, including ABBA and Madness, at their special New Year's Eve parties at the Southbank Centre in 2009 and 2010.)

Therefore, when I heard the news that Bellowhead had decided to disband after twelve years together – that Jon Boden was leaving and the rest of them didn’t want to continue without him – I was miserable, but I also understood and respected the decision. Better to quit at the very top of their game than for individual members to become frustrated, to take the core identity too far away from the audience’s pleasure, or to become essentially a tribute band playing the old hits.

It was with heavy heart that I went to the London Palladium last week for Bellowhead’s last London gig ever, but determined to drink in every last second of being in the room with them all before I would have to resort to recordings. Did I mosh? Friends, the Palladium was seated and it was only at the end that the collective will of the upper circle turned to dancing – imagine my frustration. Did I cry? Of course I did – they finished with Prickle-Eye Bush, one of the first songs I heard them sing at the Royal Opera House.

And am I sad? Yes, but less so for knowing that I enjoyed every minute of the 14 Bellowhead gigs I went to over the years (see how much of a fangirl I can be when so inspired?). The visceral sensation of moshing at the front on a sunny summer evening in 2013 at Kew Gardens, and at all the other gigs, will remain with me forever. Which I guess is the lesson, one which David Bowie and Prince fans probably understand only too well: don’t ever take live music and musicians for granted. Find them, treasure them, love them and lose your cool over them. I certainly lost my cool over Bellowhead – and found it.