Doughnuts are good for you

The Doughnut theory of economics sets out principles and practical steps towards a sustainable, just and happy world. What can classical music learn from it?

You wouldn’t think that a book on economics has much to say about classical music. Indeed, Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics – Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist doesn’t directly, but there are many fascinating arguments and concepts that can be applied if you squint a little. It’s such a progressive, positive call to action to fix the world that it’s hard not to want it to work for our sector, which is manifestly broken at the moment. I’m not an economist – the fact that I finished the book is testament to the clarity of Raworth’s arguments – so you’ll have to read her book yourselves. What follows is my very loose understanding and wild extrapolation.

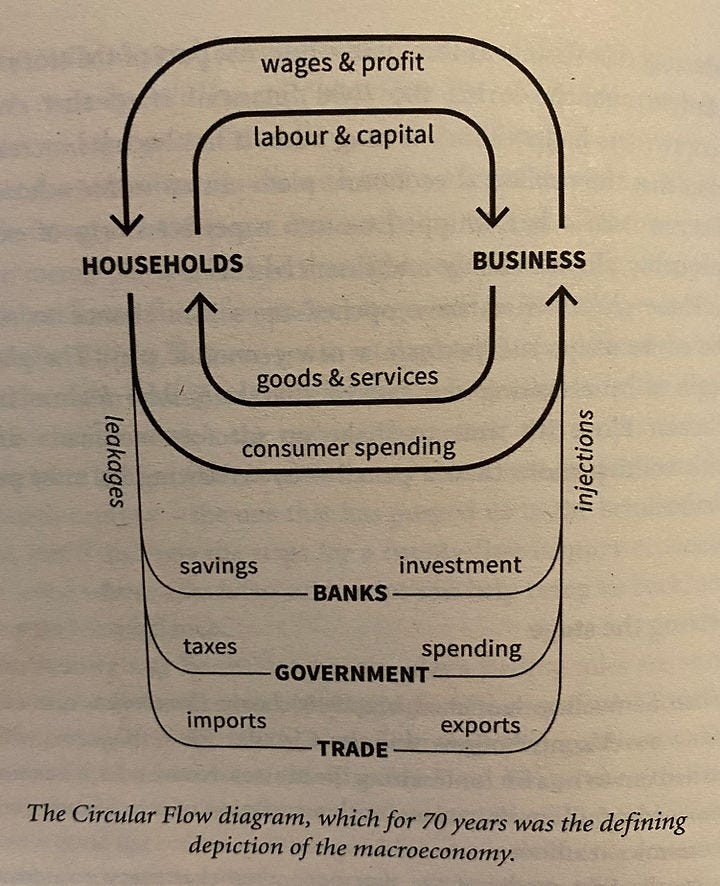

Underlying our economic world views have been models and diagrams economists use to describe the world and educate its new generations. Raworth makes the point that such illustrations often inculcate assumptions and world views, rather than leading to new interpretations and better policy. Here, for example is Samuelson’s Circular Flow diagram – the first attempt, in 1948, to describe what was to become the field of macroeconomics.

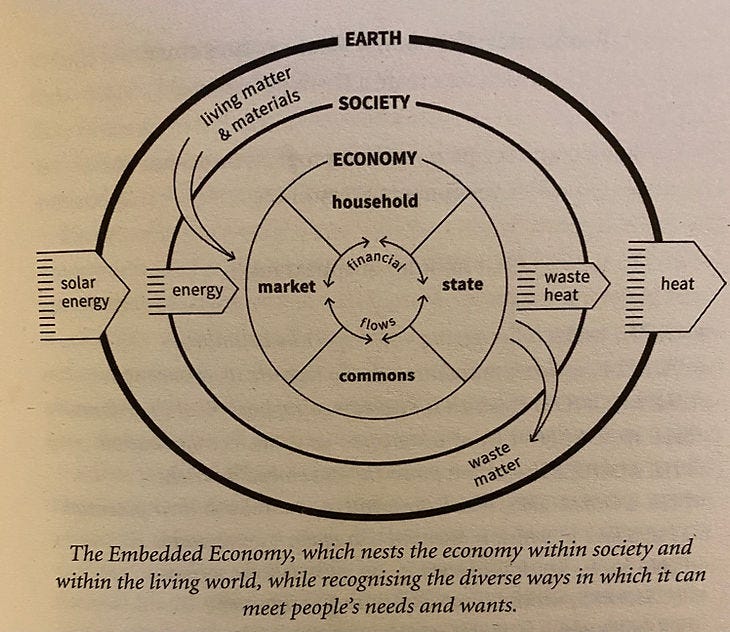

It shows a closed system whereby households work for their living and buy things with their wages, which go back to the businesses, give or take what they give to the government or put in the bank. However, it leaves out many of the resources on which we also rely – including the energy and planetary resources that make our existence possible in the first place. So she creates her own inclusive model, which she calls the Embedded Economy, which factors in elements such as the commons, society and Earth itself.

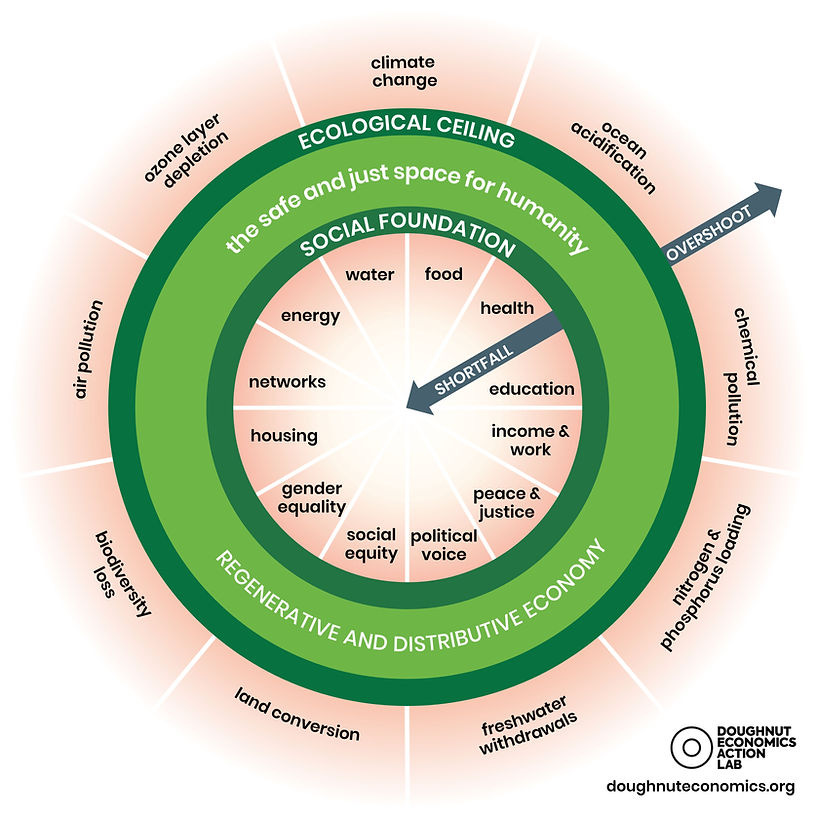

Raworth’s central argument is that for too long economists have pursued the goal of the growth of Gross Domestic Product (GDP – output), leading to wealth inequality and the perilous misuse of natural resources, and that a bigger, better goal is needed. This is where the Doughnut comes in (a ring one rather than jammy). Our goal should be living in the doughy bit of the Doughnut diagram, where everyone’s needs are met but we don’t encroach on the planet. It offers specific metrics for how we live this good life, where everyone has their physical and spiritual needs met without destroying the planet.

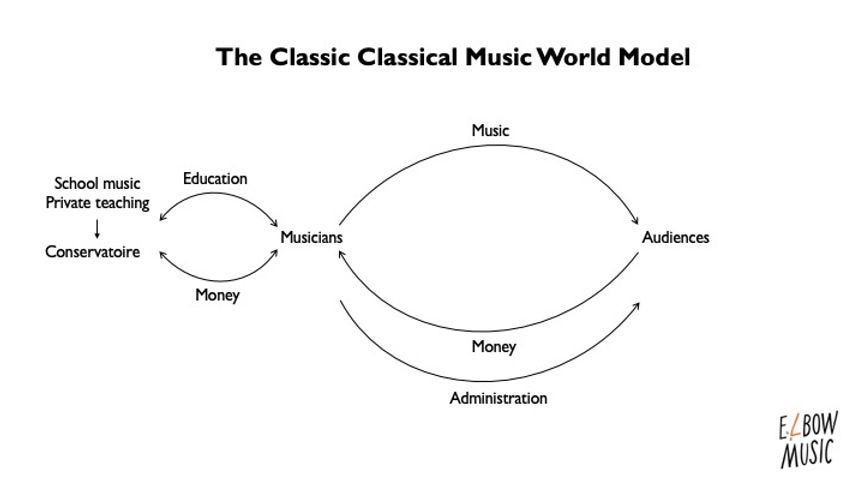

I haven’t found any models of our world, but a primitive flow diagram along the lines of Samuelson’s diagram might look something like this:

Put simply, musicians give audiences music and audiences pay musicians. That’s how it used to be, whether through live music or recordings. To the traditional conservatoire-led way of thinking, musicians either play or teach, with little crossover (I’ve written before about this paradox). Teaching is done in schools and conservatoires, and performances are given in venues and recording studios.

However, of the many things the current crisis has taught us, the most important is that the model of ‘make music, get paid’ is more fragile than we ever imagined – in one fell swoop, performance life has been catastrophically devastated. Many people are valiantly doing creative and innovative things to survive, and teaching has adapted remarkably well, but the system is broken.

What can we learn from the Doughnut? Raworth describes seven ways ‘to think like a 21st-century economist’. These have specific economic ramifications but it’s an interesting thought experiment to apply them to classical music.

1. Change the goal

2. See the big picture

3. Nurture human nature

4. Get savvy with systems

5. Design to distribute

6. Create to regenerate

7. Be agnostic about growth

Change the goal/See the big picture

In fact, the ‘make music, get paid’ system was broken pre-Covid. Streaming services make millions while musicians get paid micro-pennies; concert halls struggle to appeal to young audiences, who prefer the instant highs of TikTok; classical music has become a weapon in the culture wars, misrepresented and vilified from left and right; instrumental teaching is the preserve of the middle classes and arts subjects have been stripped from the syllabus. We need a bigger and better goal than simply being paid to make music or teach – a model that reaches far and wide and touches on the many important things that music offers. We need to change the goal, just as the Doughnut attempts to do on an even bigger scale.

Nurture human nature

Economists have always based their theories on a concept of a ‘rational economic man’ who functions only in self-interest, and Raworth describes this as inaccurate and outdated. To live in the tasty bit of the doughnut, we need a more sophisticated view of human beings and their needs and development. She asks, ‘What are the values, heuristics, norms and networks that currently shape human behaviour – and how could they be nurtured or nudged, rather than ignored and eroded.’ She cites psychologist Shalom Schwartz, who studied people across the world and found ten core values in their behaviour: self-direction, stimulation, hedonism, achievement, power, security, conformity, tradition, benevolence and universalism. All ten are present to different degrees in individuals and cultures, and change even over the course of the day. Music engages just about every single one of these, which is surely an argument for it being at the heart of any macro-economic modelling.

Design to distribute

In high-income countries the gap between rich and poor is at its highest for 30 years. So how do we how to distribute resources – whether knowledge, money or energy – more equitably? This isn’t just a charitable or moral imperative – it’s pragmatic. Raworth explains how scientists analysing natural ecosystems have concluded that the better their diversity and distribution, the more successful their entire system is.

What does this look like for classical music? We all know we need more diversity in terms of the people who do it: it seems this is finally being addressed but it must be embedded in any modelling.

Presumably, this theory also means we need diverse types, ways and formats, and that is something that we usually do well – on any given day in a big city, you would find a wide range of types of concert, whether quartets, orchestras or solo music, of music from every era. And distribution is easier than ever – the upside of the internet and digital tools that have decimated artists’ recording profits is that anyone can make a recording in their front room, or perform live, or teach, with relatively low costs attached. This has been one of the few positive developments throughout the Covid crisis, with music and music education widely available.

But is there more we can do to distribute the experience of live music, once we’re back running again, and even within the current limitations? Maybe this is where our ecosystem should rely less on venues and big organisations and more on local networks of diverse performers.

Create to regenerate

Since the industrial revolution, our systems have been based on degenerative design, raiding the Earth’s resources – ‘take, make, use, lose’. In order to sustain a relationship with the planet, Raworth argues that we have to bring emissions way down to within planetary boundaries – ‘sufficient absolute decoupling’.

The music business is fairly culpable in this matter. Should artists swan off to New York for a recital and back in a couple of days? Should orchestras fly to Japan for a tour of four concerts, skipping between each by plane? This crisis has put paid to that for now, but it’s also an opportunity to fundamentally rethink the way the business exists as a global enterprise.

There’s a certain cognitive dissonance about this for me. I would be devastated not to see the great musicians of the world in our own concert halls. There has to be some sort of compromise that involves much more local playing and more consolidated tours that use more rail travel – maybe not the months-long train tours that players used to do, but something more environmentally efficient that ensures that as a business we significantly lower the emissions we cause. This debate is only slowly emerging in the sector, and there’s still a lot of denial.

Our problem is one of regeneration, in another sense, too – of audiences and players. Raworth’s suggestion is co-optable: to be generous ‘by creating an enterprise that is regenerative by design, giving back to the living systems of which we are a part’.

Her question is ‘how many diverse benefits can we layer into this?’ instead of ‘how much financial value can we extract?’ And that to me is the big question for designing a better model for the music world. How many musical benefits can we layer in, for every person, at every stage of life, in every area? What happens when we shift our concept away from being given money to make music into this broader, more generous concept?

Raworth describes this happening not through textbooks but through innovative experiments, and the good news is that we are seeing more of these ideas and trials in the classical music world. They even seem to have increased through the current crisis. I wrote about how young stars such as Nicola Benedetti and Sheku Kanneh-Mason are taking on this responsibility here.

The generous city

A key concept of Doughnut Economics is the ‘generous city’, designed and built within the limits of its environment, offering renewable energy, affordable housing, cheap public transport, enterprise hubs and plenty of good jobs. The whole concept of value has been transformed from merely wealth into skills, knowledge, trust.

No such city exists yet, but Raworth describes an experiment in Oberlin, Ohio, which in 2009 created a set of radical goals, including saving more carbon dioxide than it produced, growing 70% of the city’s food locally, conserving 20,000 acres of green space and reviving local culture and community, among other measures. Its purpose was to improve the resilience, prosperity and sustainability of the community. All of these are constantly monitored using specific metrics, with data available on the Environmental Dashboard, online and in civic buildings. They also created a new performing arts centre – because of course the arts are central to such a vision.

If we were designing from scratch, what would our generous musical city look like? What would our dashboard look like? The improvement in well-being of elderly people in care homes? Hours of focus in the a classroom? Number of hours of instrumental teaching? Minutes of applause? Spare time spent playing by amateurs? It would certainly include emissions from musicians flying and driving.

Investment

Where will the money come for all of this? Something else this crisis has taught us, if we didn’t already know, is that we can’t rely on the UK government, which seems to be ideologically opposed to music education. In the Doughnut, regenerative enterprise does need financial investment, but from long-term investors who are looking for generating value including social and cultural, as well as fair financial return. Believe it or not, such banks exist already – Dutch bank Triodos and Florida’s First Green Bank, for example.

There may also be fresh opportunities from shifting from thinking of music as a thing we sell to thinking of it as a service or an experience. For example, I recently wrote about the String Club, which basically offers musical childcare classes and camps and has been incredibly successful – while also building generations of children who are at home with music. And I recently heard a fascinating discussion of how Opera Australia has found new audiences by marketing its performances as experiences.

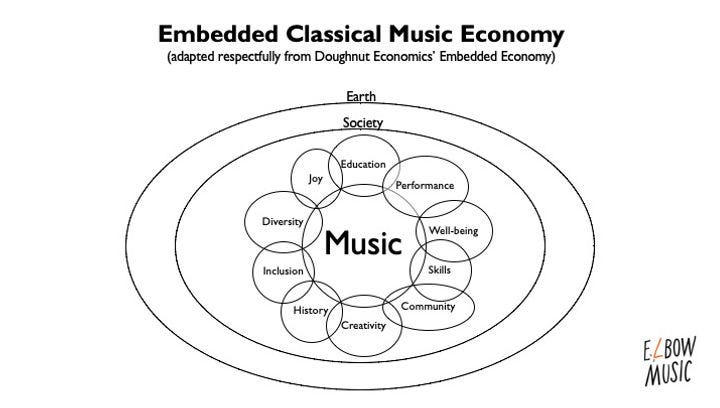

Purists will rage against using music as a means to an end rather than an end in itself but as we face an existential fight for survival, I find this argument unfathomable and irresponsible. If we love classical music we should want as many people as possible to have access to it. We have to envisage and reinvent its future rather than hanging on to the past. That doesn’t stop anyone from pursuing excellence with integrity and historical awareness – it just means opening up more possibilities to more people. Maybe something like this:

Finding the jam

What does the Doughnut actually mean for our world? Internally, maybe it can give us new perspectives and tools by which to plan and campaign. Looking outwards, how do we get involved in the wider conversations of the Doughnut Economics movement, which now includes celebrity fans such at the Pope and David Attenborough, to make sure that music is at the heart of its metrics about social values? Maybe we can even shift the paradigm from ring doughnuts to jammy ones, where music is the sweet delicious jam in the middle.